Augustine and Kuyper on Culture Building

Is This an Augustinian or Kuyperian Moment for Christian Education?

Last week (on Oct. 27), I spoke at an educator’s retreat in Richmond, VA on the ongoing importance of Augustine for the renewal of classical education. The retreat was hosted on the campus of the Veritas School, run by the Alcuin Fellowship, and sponsored by the Society for Classical Learning.

Over the years, nothing has helped me to learn about classical education more than these retreats and the conversations that have grown out of them. In fact, the book The Liberal Arts Tradition emerged from these retreats as authors Ravi Jain and Kevin Clark presented papers and seminars and sought constructive feedback.

At this retreat Dr. James Davison Hunter (of the University of Virginia) gave one of the presentations and then joined us for some two hours of discussion. Hunter said something that I noted both before he presented and then after during our discussions. He said that many think this is a Kuyperian moment but that really it is an Augustinian moment.

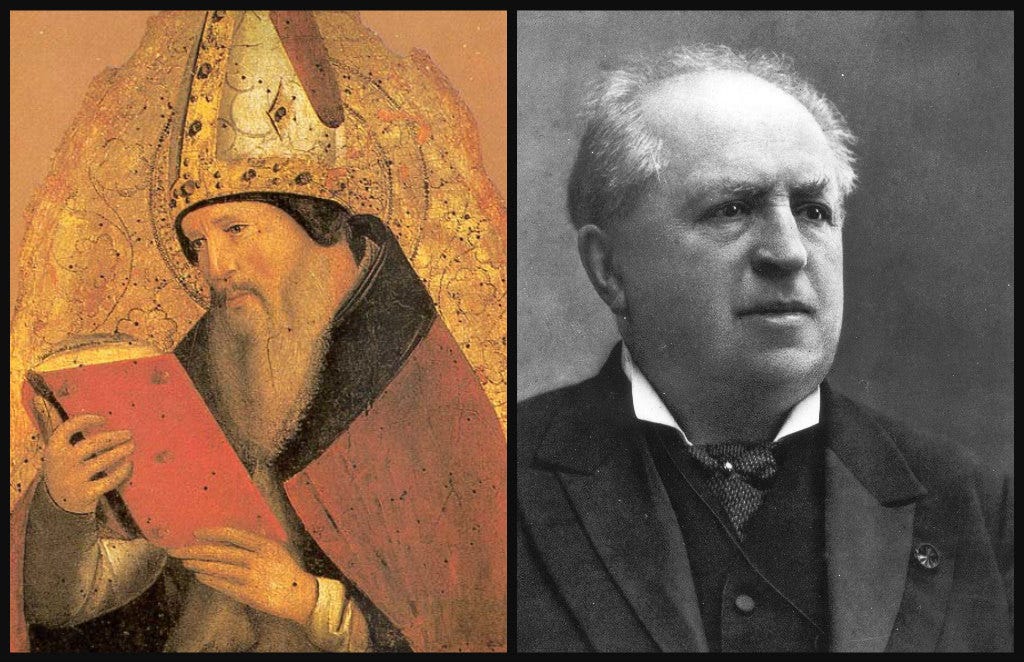

This caught my attention because my presentation, which he had not heard, made the same claim. There is a lot of good to say about Abraham Kuyper who helped found a university (The Free University of Amsterdam), established many schools, who was a thoughtful cultural and theological writer, and who was the prime minister of the Netherlands from 1901 to 1905. Anyone who has read his Lectures on Calvinism knows that he is a supple writer who uses a fine pen rather than a jumbo crayon. His last lecture, for example, on “The Future of Calvinism” is not triumphalist in the least; he notes various trends that argue for both the continued vibrancy and diminishment of Calvinism in the west. So while I note one way that I think Kuyper is reductionistic below, in various ways he is not a reductionist writer or thinker. He has skills.

Kuyper and his followers (hence Kuyperianism) are known for their hopes to create and construct Christian institutions that are fruitful and that honor Jesus Christ. No objection from me. Kuyper also thought that Christians should be active in the public square seeking to influence and bless through public institutions. Again: Nolo contendere. Why then, is this not a Kuyperian moment? In my view, it is because of the way he articulated the Christian-secular antithesis; he did not think that it was wise or helpful for Christians to work with secularists or non-Christians in the establishment and development of institutions. The distinction here can be subtle: of course Christians should love their neighbors and “work with them” in all kinds of ways from engaging in commerce, community activity, and even political activity. Kuyper thought it best for Christians to build their own institutions without interference from those outside the Christian faith.

We should note that the Scriptures do speak clearly about the differences between Christians and non-Christians. There are passages about sheep and goats, the kingdom of darkness and the kingdom of light, about “the natural man who cannot understand the things of God.” And the Scriptures also make it clear that Christ is the only God and the only Lord, and that he is supreme over all. Thus every thought should be “taken captive to Christ.” Kuyper’s most famous statement is likely this one given in the inaugural university address at the University of Amsterdam:

Oh, no single piece of our mental world is to be hermetically sealed off from the rest, and there is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: 'Mine!'

So Christians should hold to some form of antithesis. Augustine did too, as one might suspect from the title of his large book on Christian political philosophy, history, and eschatology called The City of God against the Pagans.

Again, the Scriptures do teach a spiritual antithesis. To cite just a few more examples: In the Old Testament we read “And I shall put enmity between your seed and the seed of the serpent;” “Come out and be separate and do not touch the unclean thing;” “Choose this day whom you will serve.” In the New Testament we read: “Those who are not for us are against us;” “he has rescued us from the kingdom of darkness and brought us into the kingdom of his Son whom he loves.”

Does this differentiation between Christians and non-Christians, between the city of God and the city of man preclude various forms of collaborative work, service, and culture-building between Christians and others? Augustine says no, for the two cities will always be intermingled in varying degrees. Thus, while there is a spiritual division, there is room for some limited but meaningful collaboration. We might say that while there is a spiritual antithesis there is some room for earthly synthesis. Augustine does limit the ways Christians collaborate in various institutions because he thinks that Christians will always be faithful to their Lord and his teaching and will not be able to compromise–resulting in many Christians in the Roman army and government service going to their deaths (at various times of Roman persecution) for refusing to burn incense to Caesar.

Do we note in Scripture Christians (or Israelites) making common earthly cause with others? Yes, we do on occasion. Abraham made alliances with other kings for a common defense (see Genesis 14); Solomon engaged the king of Tyre to help him build the temple and it was a craftsman from Tyre named Huram who was the leading craftsman on this massive project (I Kings 7). The New Testament assumes a practical earthly engagement from Jesus’s comment to “render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s” (Mark 12:17) to Paul's injunctions that Christians remain in whatever position they find themselves (1 Cor. 7:20) to his teaching on submitting to the authority of the magistrate in Romans 13.

The history of Christianity illustrates both a spiritual antithesis and a limited earthly synthesis, reminding that it takes wisdom to know when each doctrine applies. This relationship of antithesis and synthesis is like much of reality which is complex and intermingled whether it be the nature of light (apparently both waves and particles though who knows how) or the mind-body distinction (apparently we are both spirit and flesh though who knows how) or the the dual natures of Christ (apparently he is both human and divine though who knows how). Tertullian in North Africa in 200 AD thought Athens had little to do with Jerusalem and exhorted Christians to separate from pagan culture (antithesis) at a time when pagan temple worship was still a real temptation for Christians. Augustine in North Africa in 400 AD thought that Plato was a near-Christian, worth reading, and would have been a Christian if born after Christ (synthesis). Augustine seemed to understand in 400 AD that Christians would have to prudently determine when to be antithetical and when to be synthetical. We might ask, who knows how to do that? The answer is wisdom, and discerning the times, much as we must discern our audience when delivering a speech.

In my opinion, what we find in Augustine is more subtle than Kuyper (for all his strengths), and in one important respect truer to the actual state of affairs. Augustine advocates for the creation and construction of cultural institutions, for active engagement and service. But he also acknowledges that the city of God (Christian people generally) and the city of man will always be intermingled, mixed, and interwoven. In other words, while Christians follow Christ and his banner, they will find themselves in committees, neighborhoods, guilds, parades, businesses, governments–and yes, even schools–with those outside the church. Kuyper wanted a system that provided for tax-supported Christian schools and tax-supported non-Christian schools of various kinds, a kind of two-track body politic, unfortunately appealed to (many think by distortion) in apartheid South Africa.

In this moment of rising secularism in the U.S. many are drawn to Kuyper. I am too in several respects–insofar as he is Augustinian. I agree with Augustine and Kuyper that Christians should be building institutions. Following Augustine, this means creating schools–some that are for Christians exclusively and some that are for Christians and non-Christians together. This means strengthening existing institutions–by serving in the military, government, business, commerce. It means praying for the peace of the city, even as we seek its transformation. It means being willing to learn from modern day “Platos” or non-Christian writers and thinkers who are saying much that is true and that harmonizes with Christan teaching. It also means rejecting false teaching from those who contradict that which we know to be true, good, and beautiful and contrary to the revelation of Jesus Christ in the gospel. It means wisdom without being wishy-washy, prudence without being prude.

So I think we must note the subtle but important difference between Augustine and Kuyper: in regards to culture creation and development, Augustine proposes both/and; Kuyper proposes the either/or. Augustine remembered the parable of the sheep and goats but also the parable of the wheat and the tares that grow up together; Kuyper wants separate farms for the wheat and the tares. Here grows the wheat; there grows the tares–and no trespassing allowed.

Historically, I think Augustine was proven right or at least wise. The Christian church did work like leaven through the dough and established what we have come to call medieval Christendom, which we know was not yet then paradise (Augustine told us that too ahead of time). Historically, we should be gentle on Kuyper given that the history of the Netherlands has only progressed about 100 years since his death. Still, it hasn’t gone well for Holland. The land of Kuyper is no longer Kuyperian, if it ever was.

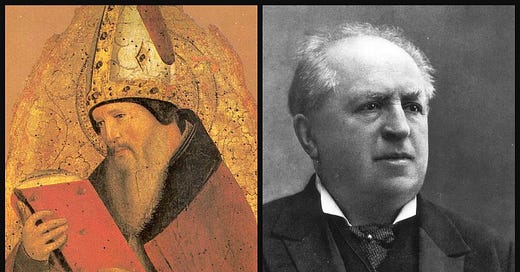

Augustine has stood the test of time, which is why we can safely say that The Confessions is a classic every Christian should read, as well as The City of God. Kuyper is worth reading too–and at this present moment–but let us give greater weight to the great doctor of the Church, Augustine, Bishop of Hippo. His essential political philosophy and eschatology (realized and hopeful millenialism) were settled beliefs across the Christian faith until the1700s. If there is a classical Christian political philosophy–it is rooted in Augustine’s City of God.

For those of you who know Augustine and Kuyper well–I beg your patience and mercy as this brief article leaves much unsaid and has resorted (for brevity’s sake) to much generalizing. I hope in the future to say more about these two thinkers with more examples, as God gives me time and strength.

I do not quite understand the use of the terms synthesis and antithesis being used this way are you saying that they exist separately without interacting? Where is the thesis statement here ? Or what don't I understand?

Thanks