This post is adapted from my new book, The Scholé Way: Bring Restful Learning Back to School and Homeschool. The book is available for pre-order here, but is available now as an audiobook here. Thanks to all those who have engaged me over the years and who are also seeking the restoration of scholé.

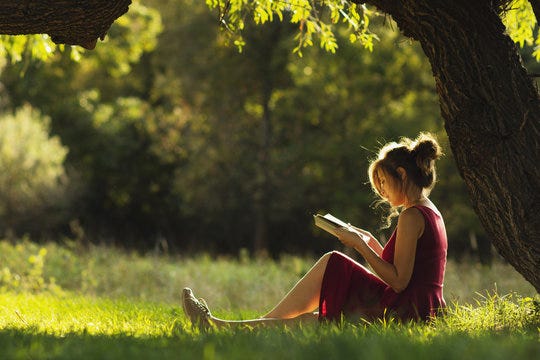

Scholé (sko-LAY) is a Greek word that defies translation into a single English word. It is most often translated as “leisure,” but that connotes “recreation” and “vacation,” which mislead us. We might say “leisurely learning,” but then we are using two words, and still much is left out. Scholé means something like undistracted time to study the most worthwhile things with good friends, usually in a beautiful place, and usually with good food and drink. It has a range of meaning because scholé is at the same time a disposition of the teacher and student, an atmosphere or setting, and an activity. It was at the heart of our understanding of what education was for about 2,000 years up until about 1900, when education was replaced by the progressive, modern “education” we have today.

Scholé is a word at the root of our English word school, yet ironically, there is no longer much scholé in our schools. This book seeks to address this critical problem in education and teaching: Modern education is filled with anxiety. How can we remove this anxiety from our students’ learning? In these chapters I suggest two ways: by recovering the traditional educational ideal of scholé and with practical solutions for bringing scholé back into our schools and homeschools.

There is an alternate path to modern education, another way to educate children that is not rife with stress and anxiety—it is the scholé way. The scholé way is the way that many have fol- lowed and traveled for centuries. While it is old, it is always fresh and ever renewing, because it harmonizes with and is ordered to human nature, to how humans learn.

Scholé is both fundamental to education and related to other fundamental elements of a traditional classical education: the curriculum of the liberal arts and natural sciences; the conver- sation contained in the great books or archived human wisdom; the cultivation of the moral and academic (or intellectual) virtues; the cultivation of wisdom; and the inherited pedagogies of wonder, memory, imitation, and practice. Even if we view education through the lens of Scholé, it is already in a dance with these other elements.

There are many rich insights into good pedagogy from the classical tradition, but I believe that the recovery of scholé is the most important of them all. I also think that by recovering scholé, many of the other classical pedagogies will be recovered in the process. Scholé is like a keystone habit: If you seek to cultivate scholé in your teaching, you will find several other habits come to you almost without noticing. We might even say, in an echo of Matthew 6:33: Seek first scholé and all these other things will be added to you as well.

It is worth repeating that scholé is undistracted time to study the things that are most worthwhile with good friends, usually in a beautiful place, and usually with good food and drink. I don’t argue that all schooling should be this restful learning or scholé, just that an important part of it should—especially in light of the fact that our schools and homeschools often have no scholé whatsoever. A portion of student learning should remain as active learning. But active learning must be harmonized with scholé.

Most of us have enjoyed moments or experiences of scholé. Perhaps you can remember an enthralling conversation with a friend discussing something pivotal and life-changing, being so absorbed in the conversation that you lost track of space and time. That was scholé. Perhaps you had a teacher who led you from wonder to thoughtful reflection and conversation that delighted your soul and inspired you to ongoing study and work. Maybe you have been in a book club with friends that has fostered deep, meaningful conversation over a great text, with good coffee and tea in a beautiful setting. That, too, was scholé.

What if these kinds of experiences could be multiplied so that your entire school or homeschool community would enjoy regular scholé? What if scholé was at the center, not the periphery, of your school and life?

Joining the Scholé Conversation

For about twenty years, I and others have been thinking, talking, speaking, and occasionally writing about our need to restore scholé. I think I came across the concept first while reading Aristotle’s Politics (especially books 7 and 8), in which he says explicitly that scholé represents the highest human activity, such that even our work is for the purpose of getting to enjoy scholé. 4 Then I began to see the idea everywhere in the classical tradition of education: It was in Augustine and Basil; it was in Gregory the Great and Aquinas; it was all through the monastic tradition of education; it was in Petrarch and Dante; it was in Introduction John Henry Newman; it was in C. S. Lewis, Josef Pieper, and A. G. Sertillanges. And reading these authors reminded me time and again that there is a Christian form of scholé in the Scriptures—from the Sabbath rest at creation to the example of Jesus and the apostle Paul.

One collaborator and fellow writer on the topic of scholé is Sarah MacKenzie, who wrote Teaching from Rest in order to help homeschool educators battle and dispel the anxiety that often besets those who teach their children at home. She subtitled the book A Homeschooler’s Guide to Unshakable Peace, and the book struck a nerve and is read annually by thousands of homeschool- ing parents. If you have not read it yet, you probably should. She addresses the soul of the teacher directly and powerfully.

Another collaborator is Devin O’Donnell, who wrote The Age of Martha: A Call to Contemplative Learning in a Frenzied Culture. His book does a fine job of describing the concept of scholé, its history, and the ways it could be recovered. Andrew Kern, too, has been an important friend, conversation partner and contributor to the recovery of restful learning or scholé.

I have finally written a book on scholé entitled, The Scholé Way: Bring Back Restful Learning to School and Homeschool that will be released this January or February. It can be viewed as a companion to books by Sarah Mackenzie and Devin O’Donnell. While MacKenzie primarily focuses on the soul of the teacher, this book seeks to help teachers bring restful learning or scholé to students by modeling it, embodying it, and creating the conditions for it. The way we restfully learn is to recover scholé, and to recover scholé is to commence the recovery of classical learning generally.

The Scholé Way views the entire educational endeavor through the lens of scholé or restful learning. I believe that it is a very helpful vantage point to consider all of education and is greatly needed today when so much education has become frenzied and stressful. However, it is not the only perspective on teaching and learning. A good classical education also pays attention to the cultivation of wonder and inquisitiveness, to embodied and liturgical learning, to the deep reading of the very best books, to cultivating conversation and friendship, and to the cultivation of virtue. Scholé overlaps or is interrelated with these other pedagogies.

Why should we recover scholé? Not simply because we want more peace and tranquility for our students (though we do). Scholé is in an important sense its own end—we all long for meaningful, peaceful conversation about the most important things. But with scholé also comes a built-in benefit and blessing: wisdom and virtue. All good education, worthy of the name education, aims at forming students in virtue—the keystone virtues of prudence, justice, temperance, and courage (or fortitude) and the intellectual virtues of love, zeal (or studiousness), atten- tion, and constancy, and humility. Education also slowly seeks to make students wise—so that they understand more comprehensively the ways of God and the ways of man, so that they discern the harmonies among the various kinds of knowledge, so that they know something about the cosmos as it really is. Wisdom and virtue grow in students when they enjoy scholé.

Students who are wise and virtuous are prepared for any good work. They have studied the liberal arts, giving them skill in interpreting and describing the world in both word and Introduction number. They have studied the natural sciences so that they can discern something of the marvels and intricacies of the cosmos. They have studied the great books so that they are familiar with the nobility and vagaries of the heart and can often “predict” the future, having become well acquainted with history and the proclivities of human behavior. Such students have learned to learn and retain a zeal for new study and exploration. Students educated this way are generally prepared for all kinds of careers and callings without focusing on the merely practical or immediately useful. Paradoxically, they are practically prepared because they have become virtuous, and virtue is practical for any job, in any country, at any time.

If we want this for our students, then we want scholé, for scholé is the best path to wisdom and virtue.