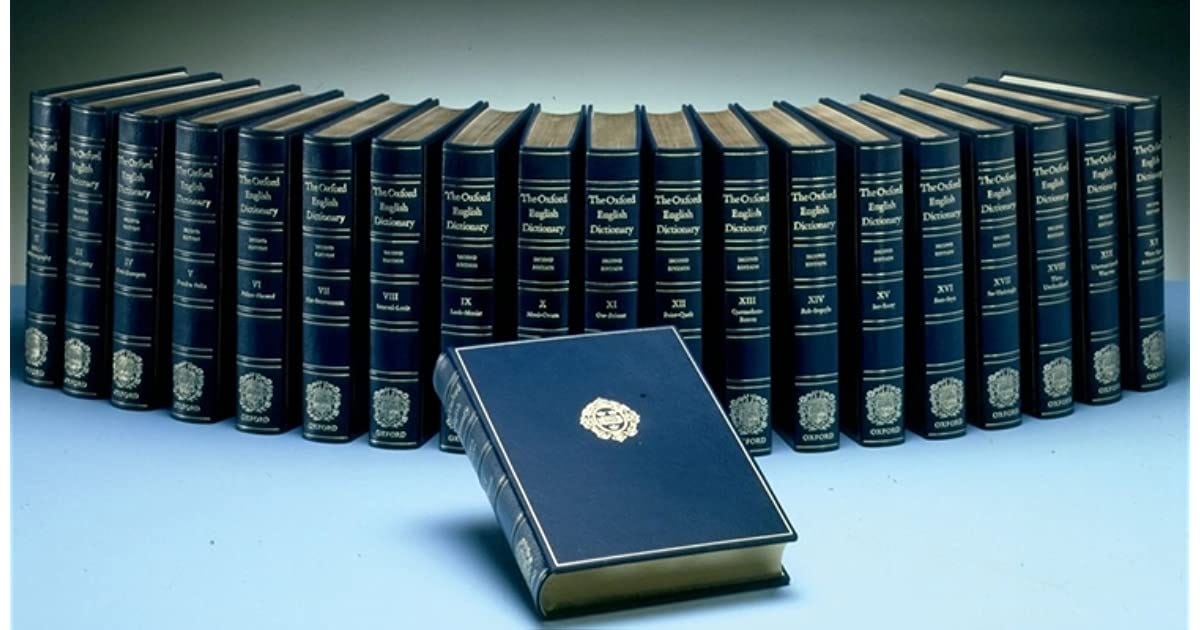

Our family has not one but three editions of the Oxford English Dictionary (the OED). I should qualify: we have three editions of the Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, and all of them were purchased used (and reasonably-priced) on the internet. Why three? Well, one for my wife and me, and one each for two of our children.

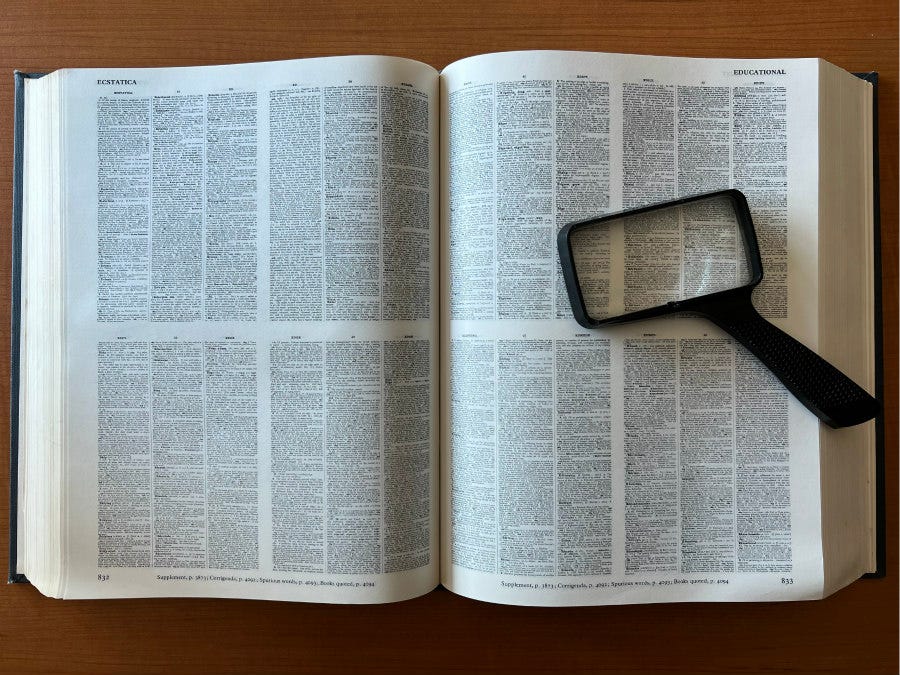

It is important to note that we have the compact edition because the entire OED is published in 20 large, hardback volumes and is priced at over $1500. We purchased the compact versions for under $50 each. The compact version comes in just two (quite large) volumes. You may ask, how are 20 volumes compacted into just two? The answer is simple: the font is about 10 times smaller in the compact edition. The print is tiny–micrographic. This is why the compact edition comes with its own high-powered magnifying glass.

The OED is the king of all dictionaries, containing over 600,000 words and growing at a rate of about 500 words per month. The story of its creation is well worth reading in the book The Professor and the Madman and the movie of the same name.

One thing more: I have an online account with oed.com. This a perk of my work, and would that all logophiles could have such an account (it cost $100 per year). At the very least, those interested could acquire the compact edition–that’s where I started.

There is a lot to love about the OED–it is extensive (the most extensive), it is historical, it is growing, it is in print, it is online, it is meticulously maintained by Oxford University Press. I would like to note two features that I love most–etymology and quotations.

First, the OED features remarkable etymologies. Every word has an origin and a history. A single word can often be a portal into the past, ushering us into a period that preceded us but in some way has also made us. This is certainly true in the world of education. Take almost any traditional word used in education and trace its origin and you will find yourself in the remarkable world of classical, liberal arts education. And once you are studying education, you are studying (from one important perspective) the ideals of a nation, people, or civilization. The way a nation seeks to educate its young reveals what that nation aspires to be.

We could start almost anywhere–with the word “education” itself. There is a deep, layered, rich story packed into this word, though most of us don’t know it–including professors of education. Let’s go to the OED and etymology for “education:”

Origin: Of multiple origins. Partly a borrowing from French. Partly a borrowing from Latin. Etymons: French education; Latin ēducātiōn-, ēducātiō.

Etymology: < Middle French education action of bringing up a child with respect to physical, mental, and spiritual development (a1380; rare before 1527; French éducation ) and its etymon classical Latin ēducātiōn-, ēducātiō rearing (of young), upbringing, nurture, (of animals) breeding < ēducāt- , past participial stem of ēducāre educate v. + -iō -ion suffix1.

Compare Spanish educación (1499), Portuguese educação (17th cent.), Italian educazione (a1498).

This etymological entry is itself a short history of education. We are already touching upon the Roman conquest of the lands surrounding the Mediterranean and the French Normandy Invasion of Britain, by which the French language (which was highly Latinate) made contributions to English. As the Romans conquered Hispania and Italia, it is no surprise that the Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian words for education are derived from the Latin ēducātiō.

The meaning of the original Latin (“upbringing,” “nurture”) is retained and extended to mean upbringing “with respect to physical, mental, and spiritual development.” This essential meaning for “education” discovered in the etymological study is then born out in the definitions offered by the OED:

Education: The process of bringing up a child, with reference to forming character, shaping manners and behaviour, etc.; the manner in which a person has been brought up; an instance of this. Also figurative. Cf. upbringing n.

Here, in the leading entry, the OED tells us that “education” means formation in character, the cultivation of virtue in children. How many of us, when we hear the word “education,” think first of formation of character? How many of us think of the way in which a child is “brought up?” This is what people used to think when they considered “education.” The OED, in its third definition, deepens this idea:

Education: The culture or development of personal knowledge or understanding, growth of character, moral and social qualities, etc., as contrasted with the imparting of knowledge or skill. Often with modifying word, as intellectual education, moral education, etc.

Here the OED notes that education is associated with culture or cultivation. Notably, it contrasts “education” with skill acquisition. Education is first a kind of personal knowledge associated with growth as a moral and social person. Now we know that it is important to acquire practical knowledge and skills but note how the tradition of the word education presents us with the moral, personal development or cultivation of a human being. That’s what education used to mean to educators of the past. Education was formation. In fact, one important synonym for education (educatio in Latin) was simply humanitas from which we derive our word “humanities.” But that would take us to and through another portal that we should resist for the moment.

We have briefly opened just one door–”education”--and find ourselves in some mystical museum where we start learning what education was and perhaps should be today.

Another great feature of the OED is the copious quotations showing the use of the word in literature over the centuries. For example, under the third definition for education cited above the OED lists these nine quotations over a 500-year period:

?1533–4 R. Saltwood Compar. bytwene iiij. Byrdes sig. Aiiijv Hystoryes calling to my rembraunce In the lytel body that vertu hydyth The grosse body a yocke to be of combraunce Of educatyon, such robustnesse rysith Demynishment of stature in vertu smilyth.

1650 W. Davenant Disc. upon Gondibert Pref. 21 Particular endeavours, onely in behalf of our own homes, are signs of a narrow morall education.

1747 M. Towgood Dissenting Gentleman's Second Lett. 5 The Child surely, does not engage for its own religious Education.

1861 J. S. Mill Considerations Representative Govt. viii. 156 Among the foremost benefits of free government is that education of the intelligence and of the sentiments.

1868 J. E. T. Rogers Man. Polit. Econ. (ed. 3) x. 116 It confounds education with the knowledge of facts, whereas it really is the possession of method.

1872 J. Morley Voltaire ii. 42 The Jesuits,..devotion to intellectual education.

1906 H. Holt Calmire (ed. 6) xii. 156 Our moral education comes from the scrapes we get into.

1958 Times Lit. Suppl. 10 Oct. 573/3 Fifteen-year-old Franzie, petite and bouncy, has begun her sentimental education long before she meets the ‘surf-bums’ on Malibu beach.

2000 B. K. Seeber Gen. Consent in J. Austen iii. ix. 107 Austen heroines go away for a certain short time and this is often when crucial education takes place.

This shows that the editors of the OED have scoured great reams of literature to discern the meaning of words so that their definitions are clearly not arbitrary. This method of creating definitions assumes that meanings of words are their use. This also means that the meaning of words change over time, which in turn prompts us to ask, how is the meaning of the word “education” changing today?

The OED still leads with education as formation. However, in the U.S. anyway, we can discern a great muddling of this word among the general population. It is no longer clear to many (most I think) that education is first of all formation and cultivation of virtue or “character.”

The OED is an education in itself, and contains thousands of pathways into history and deeper learning. What if we entered the door marked “humanities” or “school” or “learning” or “science?” I hope to do that in some future articles.

But may I ask you: What do you say that education is?