Odysseus: The Man of Twists and Turns

The Pros and Cons of Being Curious and Clever

The following is adapted from a speech I gave at Messiah College on November 13, 2024 to the first year students who are part of the Messiah Honors Program. The students are all reading the Odyssey this fall. If you have read the Odyssey I hope will enjoy it. If you have not, I hope you will soon read the Odyssey.

Where are you heading and where do you want to go? If we are honest, isn't it true that we often find ourselves stepping off the path we have decided–with clarity and finality–that we want to take? In various ways, don’t we impede our own progress? What are those things in your life that tempt you to turn aside from that path? C.S. Lewis writes:

We all want progress. But progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road and in that case the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man.

Yes, we are apt to stumble and get off-tract. But where do we want to go? In the case of Odysseus, he wants to go home.

Odysseus has given us the word odyssey. Imagine if your name was so associated with a wandering journey that your name came to mean that. If you are James, then perhaps a Jamesy would mean a wandering quest, or a Johnsy or a Maggie. Perhaps a trusty minivan would go by the name–he drives a new Jamesy.

Odysseus’ story is a story of wandering, a story of adventure and quest, a story of wrong turns, a story of seeking a way back home. The Greek word for homecoming is nostos, and aren’t we all fond of homecoming, and if we are not, don’t we still wish we had a bright, warm home that we could return to?

The word “home” settles deep in our bones. “Home” connotes, fire and hearth, welcome and refuge, order and peace. Who, really, doesn’t long for home?

Odysseus longs for home, and weeps for home, even though he is the most valiant warrior, a man strong and cunning, the most capable in battle. Odysseus did not want to leave his home for battle, even though he eventually did, as the King of Ithaca, taking with him many worthy soldiers (and sailors) from his island kingdom, leaving his young wife Penelope and infant son Telemachus.

Odysseus was so reluctant to leave for Troy–where Helen was held as a willing captive by Paris the Prince of Troy. Menelaus was the King of Sparta and the enraged husband of Helen, reputed to the most beautiful women in the known world. Menelaus insisted that all the Greek kings muster their sailors, soldiers, and ships to go to recover Helen by as much force as necessary.

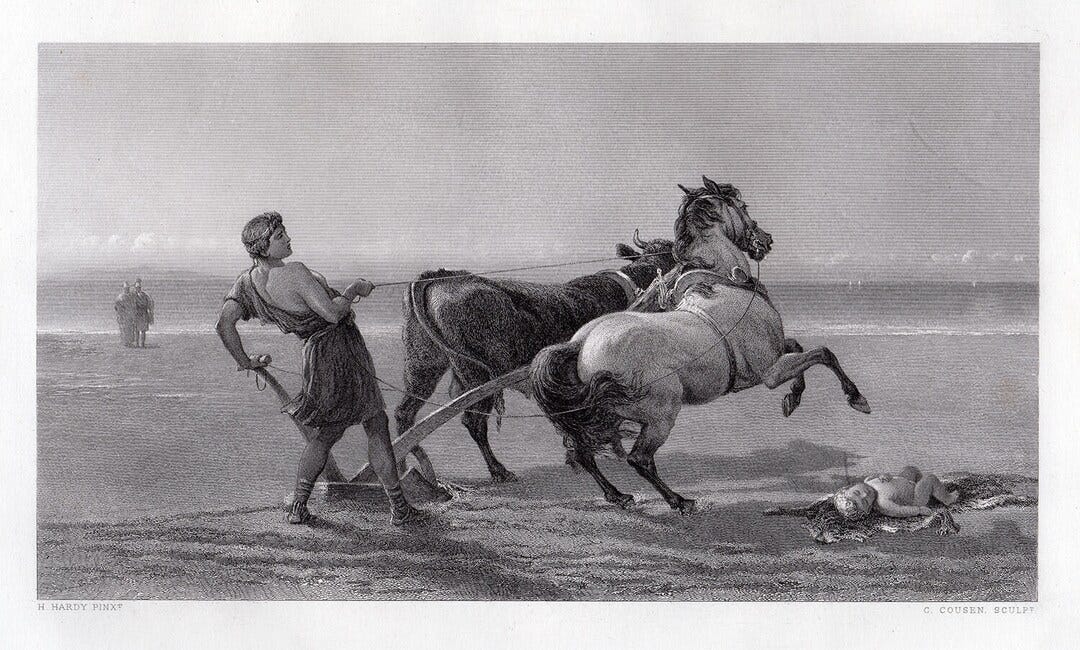

But Odysseus had his own beautiful wife–Penelope–making Odysseus very much unwilling to leave. So when called upon by a collection of Greek kings to go fight at Troy, he feigned madness, hitching a donkey and an ox to a plow and sowing salt not seed his fields. Here is a king pretending to be mad–reminding us that King David did the same thing when held captive by the Philistines, scratching marks on doors and gates and letting saliva run down his beard. And we might as well recall that David, too, loved a beautiful woman–Bathsheba–and that love for that woman brought him much trouble.

Those observing Odysseus’s madness doubted it and put it to the test by placing his young son Telemachus in the way of his plow and revealed the ruse, for Odysseus directed his plow around his young son. Alas, he was then on his way to Troy to fight the clever, scheming, wily Odysseus, the man of many twists and turns.

His wiliness would serve him and the Greeks well in the war against Troy, for it was Odysseus’s plan and scheme to send a huge horse to the gates of Troy after 10 years–yes 10 years of weary war. The Trojans debated whether or not to open the gates and welcome the horse (beware of Greeks bearing gifts) but seeing the scores of ships departing from the coast, they let the horse in–full of quietly cramped Greek warriors, including Odysseus. Yes, the famed Trojan Horse, this was the brainchild of Odysseus. You know how this episode ends–with the conquest of Troy. The ships return, finding the city already on fire. The destruction of Troy is complete. That is the short version of the story of the Iliad.

But now Odysseus must get home after 10 years of war. We might guess he is in his early 30s now and his younger wife is waiting for him to return home to Ithaca. This shouldn’t take too long. It shouldn’t but it does. And why? Because Odysseus is polytropic. This is how Homer describes him in the opening line of the Odyssey:

Sing to me O Muse of the man of many twists and turns.

The Greek word is polytropos. We know the Greek adjective poly, which means many. We see it in the words polymath (someone with knowledge of many disciplines), polyglot (someone who knows many languages) and poly this and that (polytech, polyclinic, polytheist). Polytropos means many turns. Those who have studied English and rhetoric know that a trope is the turning of phrase: irony is a trope by which we turn one word to mean another or its opposite such as “airline food,” “jumbo shrimp,” “old news,” and “virtual reality”--or “working vacation” or “seriously funny.” When we say, “She really knows how to turn a phrase” we are speaking of tropes. Even our phrase “the tropics” has a reference to the turning–in this case the turning of the globe near the equator, where a predictable climate resides, along with a great variety of delicious fruit.

Even our word anthropology retains this turning phrase, for an anthropos (Greek for man) means a turning (tropos) upward (ana). Man is apparently that creature that alone turns his head upward to gaze and contemplate the stars and think about… himself.

Odysseus is the anthropos that is not only turned upward but turned outward and downward–every which way. He is anthropos polytropos–and a formidable person viewed from any direction. And he is set before us as an ideal. He is the Greek man par excellence.

Now there are many worthy themes in the Odyssey and there are endless commentaries upon them–homecoming, hospitality, heroism, justices, prudence, temperance, courage. But if Christ is presented to us by Pilate as The Man (Ecce Homo), Homer presents us with Odysseus (Ecce Anthropos). We know the gospels present us with Christ who has turned his face like flint to Jerusalem and the cross. After Troy, Odysseus turns his face toward home, but not only towards home.

How does Odysseus turn? First, he is turned by others, namely the god Poseidon, the god of the sea, who has it out for him because Poseidon is opposed to Athena, and Athena has taken on Odysseus as her pet project, her current obsession. The drama played out by Poseidon and Athena is a 10-year affair that gets added to the 10-year war at Troy, making it 20 years before Odysseus will return to the shores of Ithaca.

We hear the tale of his 10-year odyssey when near the end of his travels he finds himself detained at the kingdom of Phaecia at a long banquet in which he is prodded to tell his tale. He tells his tale to King Alcinous and Queen Arete and their guests, and in the process to us as well.

As soon as he left Troy, Odysseus tells us, Poseidon brings a twisting storm that hinders Odysseus’s singular focus to return home to Penelope and Telemachus at Ithaca. And well he should return home, because after 10 years, there is now a band of 108 available bachelors anxious to marry Penelope and become king. They are squatting each day at her palace demanding daily feasts and demanding that she choose one of them to marry. After all, it has been a long time, and Odysseus is clearly not coming home.

Poseidon sends him crashing here and there.

He ends up marooned on an island with a beautiful goddess, Calypso. Though a mortal, she is quite taken with him, and provides for him sumptuously, offering him her body (which he accepts as if he had no choice), fine food, and beautiful setting–all for seven years. This seven year interlude only serves to make the suitors back in Ithaca more antsy and Penelope more despondent. Calypso even offers to make Odysseus immortal–and who wouldn’t take that offer? Not Odysseus. He weeps for Penelope, longing to return home, weary first from war, and now weary after seven years cavorting with a goddess in paradise. What kind of man is this? Has he not come to his senses, much like the prodigal son? He is ready to return home after lusty living but not as a servant but as the rightful king of Ithaca.

With some help from Athena (and Hermes, the messenger god) he is set free from Calypso on a raft he has made with his own hands–he is crafty in this way too. Poseidon is still allowed to buffet the seas and make his journey a twisting tough go, but he is delivered exhausted, ruined, and wrecked on the sea shore of Phaeacia. There he is welcomed into the palace of one king Alcinous (and his wife Arete–the queen of virtue) where he is given the opportunity to tell his long story.

So we can note that Odysseus twists and turns–on the sea, in large part thanks to the schemes of Poseidon. But it is not only Poseidon who turns his ship; Odysseus himself will turn the rudder. He turns his ship aside, when we expect he would or should not.

He turns aside on several occasions, delaying his return. He turns aside to explore the land of the Cyclops, a fatal decision of several of his men who end up being gobbled by the cyclops named Polyphemus. In this case Poly is blended with Phemus– Polyphemus which means many times spoken of or renowned. When Polyphemus asks Odysseus his name, Odysseus answers that his name is “No-body” which in Greek is Outis. When Polyphemus (who loses his one eye on account of Odysseus) cries out for help, he yells “Nobody is attacking” me and no help comes. Ironically, it is Odysseus whose name becomes renowned, the “nobody” who becomes somebody indeed. After all, you know the name Odysseus, but will you remember poor Polyphemus?

What is in a name? It is a question the Odyssey asks. Does your name mean something? Will your name be remembered? The Greeks are concerned to be remembered; the dead hope to live on in the memories of the living. Who will remember you? Will God remember you? The thief on the cross next to Christ cries out, “Remember me O Lord when you come into your kingdom.”

The name Odysseus means to us now one who wanders and tries to return home. And so we recognize ourselves in him, because we too are trying to find our way… home. Christians confess this, knowing that our citizenship is in heaven, and since the time of Adam and Eve, we have been seeking a city whose Architect and Builder is God. Christ promises to bring us back to the garden, back to a kingdom, back to what we long for as home.

But the name Odysseus means literally “the one who suffers” or as Odysseus himself tells us “the son of pain.” We are reminded that Christ descended to become one of us, before ascending again to the Father. He was made like us in all respects, hungered, thirsted, and suffered want, and simply suffered as we all do. He is called the man of sorrows, well acquainted with grief. He, too, is a son of pain. This is one way the ancient Christians (and those were of Greek blood) read such passages in the Odyssey.

Clement of Alexandria, living in the 200s AD–and Greek–describes how Greek philosophy led the Greeks to the Christian faith:

Perchance, too, philosophy was given to the Greeks directly and primarily, till the Lord should call the Greeks. For this was a schoolmaster to bring 'the Hellenic mind,' as the law, the Hebrews, 'to Christ.' Philosophy, therefore, was a preparation, paving the way for him who is perfected in Christ.-- Stromata

We are familiar with the passage where Paul says that the law was our tutor to bring us to Christ (Galatians 3:24, 25). Clement says Greek philosophy does the same. As Louis Markos shows in his book, Myth Made Fact: Reading Greek and Roman Mythology through Christian Eyes, Greek literature at the very least reveals a yearning that it fulfilled in the Christian faith.

What was Odysseus yearning for? To return home to Penelope. In light of this yearning, Odysseus arguably should not have turned aside to explore the land of the Cyclops. Why did he make this turn? He was curious. Don’t turn your attention to those things that make you curious? It may come as a surprise to some, but some of the Greek and Roman moralists before Christ regarded curiosity as a vice. Sometimes curiosity seems to lead to important insights and discoveries; sometimes it is destructive and will kill the curious cat, even one with nine lives.

Odysseus says that he wanted to learn about the customs and laws of these Cyclops.

I called a muster briskly, commanding all the hands,

“The rest of you stay here, my friends in arms.

I’ll go across with my own ship and crew

And probe and the natives living there.

Who are they—violent, savage, lawless?

Or friendly to strangers, god-fearing men?”

What could be wrong with this? He seems to be engaging in a bit of anthropology. Anthropology is a fine study, but when is it a fine study? Wasn’t he weeping to get back to Penelope?

The ancient philosophers made a distinction between curiositas and studiositas–curiosity being a vice and studiousness being a virtue.

Dante, for examples, places Odysseus in the Inferno for this vice which had conquered him:

Nor fondness for my son, nor reverence

For my old father, nor the due affection

Which joyous should have made Penelope,

Could overcome within me the desire

I had to be experienced of the world,

And of the vice and virtue of mankind;But I put forth on the high open sea

With one sole ship, and that small company

By which I never had deserted been.

He later turns aside to explore an island when he spots smoke rising from somewhere in the interior. Where there is smoke, there is…..? Odysseus again is curious. As it turns out, this smoke rises from the chimney of an enchantress named Circe. Her specialty is turning men into pigs, and she is happy to employ this skill, turning all but one of Odysseus’s men (Eurylochus) to such creatures. This is a problem that will take time to sort out. He is able to sort it out because he is wiley and crafty and has regular help from a wiley and crafty goddess–Athena. Athena tells him a secret or two about how to fend off Circe with potion and some choice words. Odysseus manages to foil Circe and have his sailor pigs turned back to men.

In fact, we learn that Athena seems attracted to Odysseus because she is like him in this respect, a fitting mortal-immortal pair.

Toward the end of the journey, she reveals herself plainly to Odysseus and they exchange these fitting words:

Any man–any god who met you–would have to be some champion lying cheat to get past you for all-round craft and guile! Your terrible man, foxy, ingenious, never tired of twists and tricks–so not even here on native soil, would you give up those wily tales that warm the cockles of your heart! Come, enough of this now. We’re both old hands at the arts of intrigue. Here among mortal men you’re far the best at tactics, spinning yars, and I am famous among the gods for wisdom, cunning wiles too. Ah, but you never recognized me, did you? Pallas Athena, daughter of Zeus–who always stands beside you, shields you in every exploit.

Athena is present with Odysseus every step of the way, but she only intervenes on her own terms, seemingly enjoying the drama she, to a very large extent, oversees. She can appear as a mentor (actually as Mentor) or even a ship captain as needed. She can make Odysseus seem stronger, younger, and taller. She can surround him with a mist when it is advantageous for him to go unseen. She can add curls to his hair (yes she does this at least once). When Odysseus is not sure what he should say, Athena assures him he will be given the words needs when he needs them, recalling to mind then Christ tells his disciples in Luke 12:

When you are brought before synagogues, rulers and authorities, do not worry about how you will defend yourselves or what you will say, for the Holy Spirit will teach you at that time what you should say.

What Greek reading the Odyssey would not think it superb to have a daughter of Zeus with you at all times to guide you, protect you, and give you the right words to say? It turns out this longing is fulfilled in the coming of Christ and pouring forth of the Holy Spirit. Christ says, I will not leave you as orphans, I will guide you to all truth. All authority on heaven and earth has been given to me… and I am with you always even to the very end of the age.

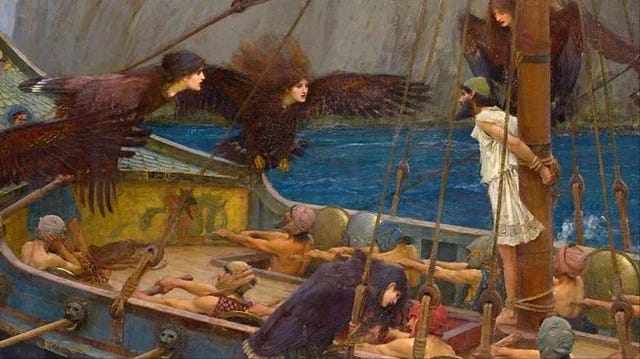

If we have any doubt that Odysseus is a lover of curiosities, all doubt should be removed when he hears about the sweet songs of the Sirens–songs so beautiful that they cannot be resisted even though they call you toward an unsavory death. He is determined to have his cake and eat it too, or hear the siren song and not be eaten by the sirens, which is precisely their custom.

“Bind me to the mast,” he tells his sailors (those who were just recently pigs) “but plug your own ears with wax so you will not hear the sweet, irresistible songs of the sirens.” Strapped to the mast he sails by the sirens and hears the enticing music and even calls out to have the sailors unbind him so he can heed the Siren’s words that would have killed him. Crafty man that he is, he succeeds. Do you want to be like him? Have it both ways?

Did Christ, bound to a tree, do anything similar? He doesn’t have it both ways (or did he?)–but endured the cross and scorning its suffering for the joy set before him. He descended to hell and did succumb to an unsavory death, but in so doing triumphed over the principalities and powers. He was the Son of Pain, but as the Centurion before the cross said, he was also the Son of God. This one could die and travel to the underworld; but this one could rise again to life, and give life–so perhaps he did have it both ways, dying and living again but then giving life to the world, a third way.

Odysseus, too, traveled to the underworld, directed there by the goddess Circe, but he seems all too happy to take this underworld adventure. Is there anywhere this man won’t go? Circe tells him to consort with the dead sorcerer Tiresias to learn how his wife and son are getting along without him at Ithaca and to get further counsel about how to successfully proceed home.

If you were offered a trip to the House of the Dead, would you take it? What a story you could tell when you came back! Would we all gather around you to hear your report?

At this point, it is good to remember how much we all love stories–and what story would be more interesting than a tale of your visit among the dead? One chief setting for the Odyssey is story-telling: for much of the book Odysseus is seated at the banquet table at the palace of King Alcinous recounting his back story of wandering adventure–including his interviews of famous dead people. At one point in the telling of the tale, King Alcinous himself breaks in and says:

Keep telling us your adventures–they are wonderful.

I could hold out here til dawn’s first light

If only you bear, here in our halls

To tell the tale of all the pains you suffered.

So the man of countless exploits continued on.

Whatever else this is, it is entertainment. In an age before radio, TV, and the internet–and ChatGPT–this was a good way to spend an evening. The Odyssey itself was recited (with musical accompaniment) around roaring fires, and around many an aristocratic table, laden with food and wine. Without much else to do, who wouldn’t want to hear tales of countless exploits–including visits with the dead?

We are all aware of our own coming death. Sometimes we push away this awareness but it is always there somewhere, lurking. As Franz Kafka says somewhere, the meaning of life is that it stops. What does it mean to die? We don’t know because no one has ever lived to tell about it. Well, except Odysseus in the Odyssey, the Aeneid, The Divine Comedy, C. S. Lewis’ Great Divorce, Milton’s Paradise Regained, and the four gospel writers. And the Lord of the Rings trilogy (recall how Gandalf the Grey returns as Gandalf the White).

Odysseus is curious even while in Hades. He wants to meet the famous dead. He wants to see his dead mother (Anticlea), and he does. He hears about how she died of grief on Ithaca waiting for her son to come home. He hears that his father Laertes is also mourning in grief for his son, dressed in rags and sleeping among piles of leaves. Odysseus weeps and seeks to embrace his mother three times, but she is a misty phantom.

But Odysseus will not waste this opportunity to enjoy himself. Even if you’re in hell, why not live a little? He summons great heroes and tragic figures from the past including Sisyphus and Tantalus; he hears a tale of woe from Agamemnon who was murdered by his wife upon returning from Troy, and who advises Odysseus not fully trust his wife or any woman. Still, angry about his deceitful murder at the hands of his wife and her lover,, he asserts: “Now it the time to stop trusting all women!”

He meets up with the sorcerer Tiresias who tells him how to get back to Ithaca safely, though alerting him to the great deal of suffering that awaits him—including the loss of his entire crew. This does not seem to bother him enough (in my opinion) and he weeps no tears for the coming demise of his crew, but rather proceeds without delay to interview more interesting and famous persons in Hades–what an opportunity!

And they are not at all happy. Odysseus is able to talk with his former warrior comrade Achilles who fought valiantly at Troy. Achilles is the greatest of the dead, described as a ruler of the dead. Would that be a privilege to lift one’s spirits–to be the greatest and most renowned among all the dead? Odysseus greets Achilles as if he were a king in his palace:

But you, Achilles,

There’s not a man in the world more blest than you–

There never has been, never will be one.

Time was, when you were alive, we Argives

Honored you as a god, and now down here, I see

You lord it over the dead in all you power.

So grieve no more at dying great Achilles.

I reassured the ghost, but he broke out, protesting,

No winning words about death to me, shining Odysseus!

By god, I’d rather slave on earth for another man–

Some dirt-poor tenant farmer who scrapes to keep alive–

Than rule down here over all the breathless dead.

This, some will know, was the passage Milton likely had in mind when he has Satan proclaim: “I would rather reign in hell than serve in heaven.” The Apostle Paul, contemplating his coming death says, “For me to live is Christ to die is gain.” Achilles, for his part, contradicts both Milton’s Satan and the Apostle Paul: For Achilles to serve on earth is better than to reign in hell. For poor Achilles, there is no hope of heaven; to die is certainly a great loss, as it was apparently for all of the Greeks and Romans–even the stoics like Marcus Aurelius who says time and time again in his private diary (The Meditations) that death is fine, death is according to nature, and comes for all. He has to tell himself this over and over again for twenty years. Clearly, even for a fate-friendly, steely stoic like Aurelius, death is not gain, but an encroaching loss that he can’t shake. Can you shake it?

Or are you like Achilles, who would argue even with a stoic: No more winning words about death!

It turns out that the dead are as curious as Odysseus. They are all itching to talk to a living man–and it is unheard that a man from above would visit them below. They want news, and they want perhaps just anything new amidst their mundane subterranean existence. Agamemnon after his brief tirade against trusting women, immediately wants new about his son:

Enough. Come, tell me this and be precise.

Have you heard news of my son? Where’s he living now?

Achilles, too, after insisting he would rather be a living slave that a ghost king does the same:

But come, tell me news about my gallant son.

Did he make his way to the wars,

Did the boy become a champion–yes or no?

Apparently there is precious little news that makes it down below. But here is a living man, come to visit. He is something special–he is shining Odysseus. If he breached the walls of Troy with the horse trick, might he have a trick to play on this kingdom of the dead? Maybe this time a Hades Horse that they could all secretly climb in and then be led out by crafty Odysseus the liberator of hell? Do they have any hope of being freed? If Orpheus could so charm Hades with his beautiful music that he granted leave of hell, could Odysseus with all his ingenious craftiness find a way to lead them out? If he was so favored by the gods to be granted a pass into Hades, could he possibly grant them a pass out? No, apparently this does not even enter their minds. But does it enter yours?

Did those in the palace of Alcinuous, hearing this tale being told, hope for a moment that the dead could be freed? Did the countless Greeks who heard the Odyssey recited around fires and laden tables, hope at this moment that the story might shift, and that Odysseus could not only leave hell, but take some of its captives with him? What did the Greek man, woman, or child, hearing this story think in 400 BC about their own dead parents and grandparents, or about their own approaching death?

Tiresias tells Odysseus not only about the ultimate success of his voyage home but about his final days and his own death:

He is told that he will live until a ripe old age and then give up his life peacefully and painlessly, surrounded by those he loves. That seems to be the best a man could hope for.

And at last your own death will steal upon you…

a gentle, painless death, far from the sea it

comes to take you down, borne down with the years in ripe old age

With all your people there in blessed peace all around you.

In the Orthodox Church we pray every Sunday about our coming death.

PRIEST: That we may complete the remaining time of our life in peace and repentance, let us ask of the Lord. CHOIR: Grant this, O Lord.

PRIEST: A Christian ending to our life, painless, blameless, peaceful; and a good defense before the dread Judgment Seat of Christ, let us ask of the Lord.

But we do so before an icon that shows Christ descending into hell, breaking its chains, and setting free those captured there beginning with Adam and Eve, whom he takes by their limp wrists and pulls out of hell. This icon is called the “harrowing of hell.”

We all turn in many ways, in ways we would rather not and often in ways we don’t understand. We are all polytropic. We turn aside, and we turn back. Paul says that he doesn’t understand what he does, saying “what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do.” Then he asks in apparent desperation, “Who will rescue me from this body that is subject to death?”

Paul’s answer is the answer that wasn’t yet available to Homer, his Odysseus and his Achilles, and his wide and vast audience across the centuries–not until the new Orpheus was born, and then died and then visited the kingdom of Hades to destroy and set its captives free. And he did this not by playing beautiful music but by the ultimate scheme that tricked the devil and apparently surprised the angels: by dying and rising again, conquering death by death. No such scheme was imagined by Odysseus or Athena or Zeus.

How does Paul answer his own question: “Who will rescue me from this body subject to death?” Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!”

This one calls us to turn aside, to turn away from our own weary wanderings and turn to him. We are all polytropic, turning away when we should turn to, allowing our curiosity to distract and sometimes to derail us. Come follow me, he says, and we follow him to hell and then back. This turn–it turns out–is a return, a homecoming, a nostos.

Christ is the new Orpheus, he succeeds where Odysseus had no hope of success. Christ was born into the Greco-Roman world, in Palestine where the languages were Aramaic, Latin, and Greek, the world of Hebrew culture, Roman law, and Greek myth. As the church exploded, it was packed with thousands of Jews, but even more with thousands of Romans and Greeks–Roman and Greek pagans, who came to see Christ as the fulfillment of all their mythic, nostic yearnings.

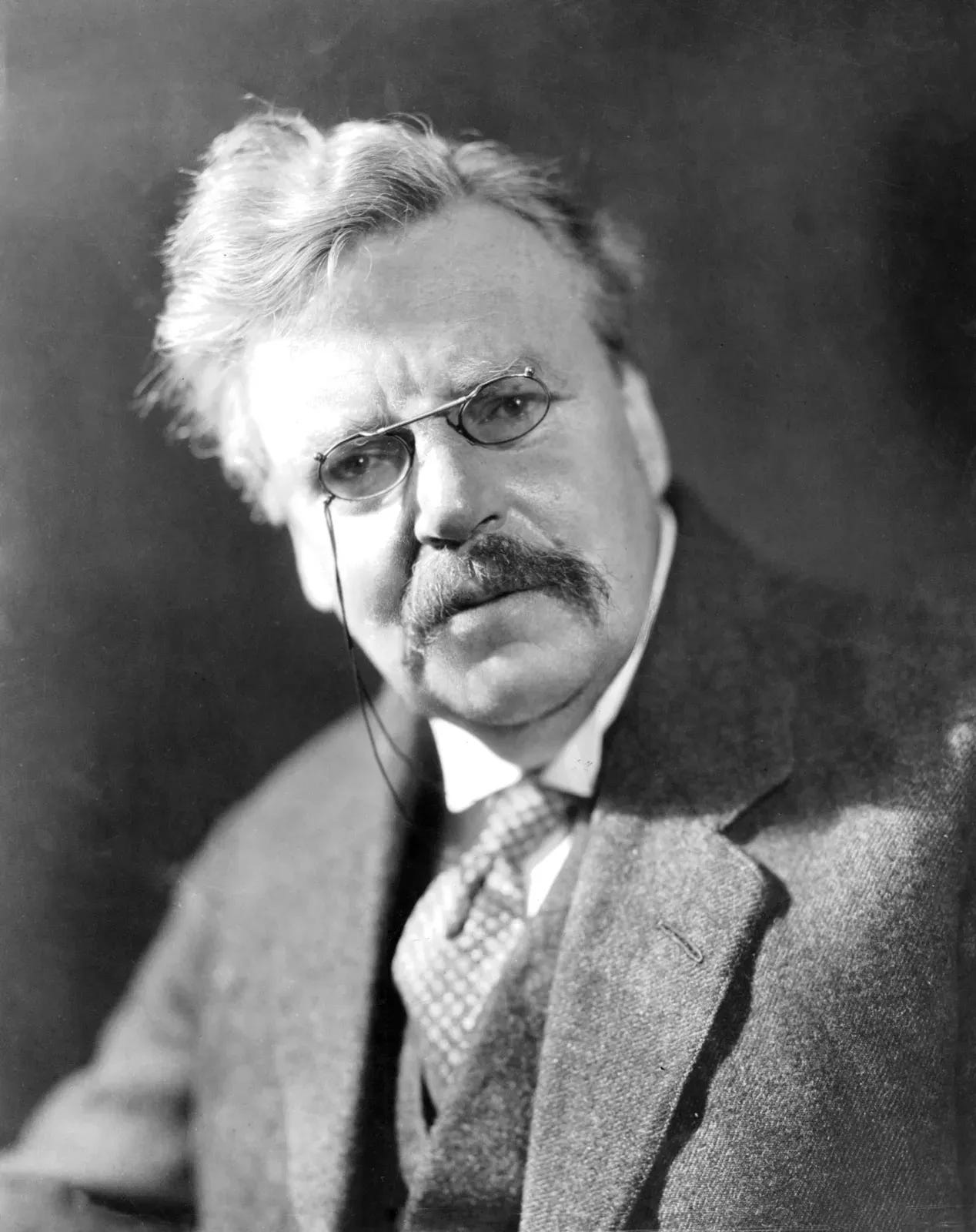

Once G. K. Chesterton, in a debate in the British press, was told by Lowes Dickinson that the British should reject Christianity and return to paganism. “Let us all become pagans, Chesterton replied, they all became Christians.”