Introduction

This article is modified from a speech I gave in July, 2024 at the conference of the Society for Classical Learning. I am grateful to SCL for the invitation to give this presentation.

I contend that education is like hospitality and healing. Christians are called to offer hospitality to those in and outside the household of faith and this hospitality should be offered through our homes, churches, and schools. We are commanded to be careful to show hospitality to strangers remembering that some had entertained angels who appeared as strangers. (Heb. 13). On the day of Judgment we will be examined on this issue (Matt. 25).

Hospitality and healing are forms of showing love: love of the stranger, and love of the sick. In this presentation, I will not try to prescribe how your school should show hospitality, though I will address this concern in my breakout session. How should you show hospitality is an important question. But the critical point is that you do show hospitality.

Why did the Society for Classical Learning dedicate a conference on Classical Christian Education to the theme of hospitality and healing? Because our country is becoming increasingly estranged, and hospitality is loving the stranger. Because our country is seriously wounded and in need of healing. This is one good reason for calling up this traditional quality of Classical Christian Education. But it is not the only quality; it is an attribute in harmony with several other attributes.

Classical Christian Education is the raising up of a child to full maturity and humanity and virtue. What endeavor is bigger, wider, deeper than that? It includes multiple dimensions–just as the church has multiple dimensions. The church is described with a dozen similes: a pearl, leaven, tree, body, an ark, a table, a bride, flock of sheep, a temple, vine, a household, an army. Christian education and thus Classical Christian Education, partakes of all these things.

In these polarizing estranged times, some note that we are in the midst of a culture war, as we are. This will call forth the martial imagery that sometimes is used in Scripture: we are soldiers under command, Jesus is the victorious king of kings, and the gates of hell will not prevail against us. Does education involve battle? Yes it does for we are training students who must war not primarily against flesh and blood–but against the powers and principalities and their own flesh. They must not be unaware of the schemes of the devil, but be equipped with the armor of God so that when the day of evil comes they can stand. The martial metaphor makes some sense but don’t regard your school as merely a military camp. You must bring healing through education but don’t regard your school merely as a sick ward. You are right, however, to animate everything with love, for Christians must love even their enemies (personal or political) and love even the stranger as themselves. And that means hospitality.

That is the surprising teaching of Leviticus 19 where we read:

But the stranger who dwells with you shall be to you as one born among you; and you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt. I am the Lord your God. (Lev. 19:4)

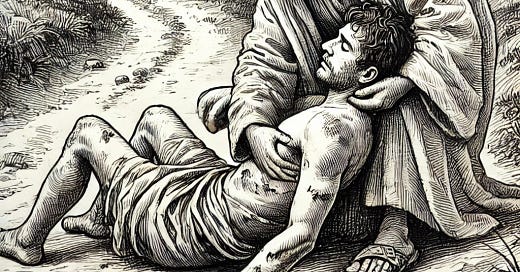

This is retaught by Jesus when he tells the parable of the Good Samaritan to a questioner who was an expert in the law, but conveniently forgot this verse.

For centuries, Christians have tried to love the strangers in their midst, offering them not just a meal but an education. We have not always done it well–and sometimes we have done it poorly–but Christians were the first people (and for a long while the only people) who sought to provide an education to everyone. You think hospitals have always existed? Christians invented that in the fourth century. You think orphanages have always been around? Christians invented them. You think education should be for every child? That is a Jewish and Christian idea.

Christians know that what we enjoy as a possession we have no right to keep unless we give it away–freely you have received freely give. We remember the parable of the talents–we are in danger of losing what we don’t invest. This is true especially of those who have been given much–to whom much is given much is required. This is true, therefore, of those schools among us who are blessed with students and wealth: You had better start giving what you have away or you are in danger of losing it. We remember the parable of the farmer who stored up his grain saying to himself:

And I will say to my soul, “Soul, you have ample goods laid up for many years; relax, eat, drink, be merry.” But God said to him, "Fool! This night your soul is required of you, and the things you have prepared, whose will they be?" So is the one who lays up treasure for himself and is not rich toward God.” (Luke 12:19)

We know that Christians are not called to prepare big barns or laden tables only for themselves, but will go to the highways and byways if necessary to bring people to the prepared table. Christians invite the stranger in.

Consider how Jesus does the same, famously in these words.

Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn (discite in Latin, mathete in Greek) from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light. (Matt. 11:28-30)

Regress and Progress

Scripture and history teach us that education is interwoven with hospitality. As we look back on what our brothers and sisters have done in the past, we will find this to be so. Christians were the first to challenge and then try to eradicate human trafficking and slavery; Christians were the first to offer education to everyone. To recover classical education is really to recover education–how can we not offer it to everyone–especially the least of these our brothers and sisters? Adler said if classical education was the best for the few isn’t it the best for all? Well then what about the least of our brothers and sisters?

If we restore education as hospitality, I believe it will result in a revolution in the sense of a turning back that is simultaneously a rolling forward.

Chesterton says, Every revolution is a restoration; Lewis says when we are lost the quickest way forward is to return home:

We all want progress. But progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; and in that case, the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man (Mere Christianity)

A rich Christian culture partakes of the Church, and the Church is the body of Christ. Christian culture exudes the “fragrance of Christ” – it is an aroma, it is a new city, it is a banquet, it is a tree opening its branches for the birds of the air. It is the washing of feet and hands; it is the adoption of children, the building of hospitals, the creation of schools, the writing of poetry, painting frescoes, the composition of symphonies.

As we recover Classical Christian Education, we are restoring hospitality, and we are also rejuvenating a Christian culture. Note the re words we use. We are doing a lot of things again–we are repeating what our predecessors have done, but with new twists and variations according to our circumstances in the 21st century. We use words like recover, renew, restore, rejuvenate, repair, revitalize, recreate.

Let me suggest some organic ones: reseed, replant, reforest. Many are sharing provocative ideas about how we can sow some heirloom seeds in this cultural moment.

Every age, if it is to flourish, returns, relearns, restores, taking the past forward and finding the past replanted in the future. Renewing classical education is a deliberate, slow process; children grow slowly as do trees. Renewing classical education is a kind of reforestation. You will notice little in 10 months–but a good deal in ten years and something remarkable in 50.

Judah to the Present Day

There is much to learn about education as healing from Christ speaking to us in Matthew 25 when all the nations will be gathered before him, and from Luke 10 when he shares a parable about a merciful Samaritan. But first, let’s consider Jeremiah. What we see now, we’ve seen before, so let history and Scripture instruct us. Consider what we have seen 2600 years ago in Judah. When Jeremiah was writing in about 600 BC, things were not well in Judah.

Jeremiah says in Jeremiah 6:

“From the least to the greatest,

all are greedy for gain;

prophets and priests alike,

all practice deceit.

They dress the wound of my people

as though it were not serious.

‘Peace, peace,’ they say,

when there is no peace.

Are they ashamed of their detestable conduct?

No, they have no shame at all;

they do not even know how to blush.

So they will fall among the fallen;

they will be brought down when I punish them,”

says the Lord.

“Look, an army is coming

from the land of the north;

a great nation is being stirred up

from the ends of the earth.

Jeremiah says this before the Babylonians were to come down from the north and destroy Jerusalem (in 586 BC) and exile the Jewish population to Babylon. The state of things was not good, and Jeremiah makes it crystal clear what is going to happen unless there is clear, clean, pervasive… repentance.

This is the same chapter where Jeremiah urges the Jewish people to return to the well-worn, good paths:

This is what the Lord says:

Stand at the crossroads and look;

ask for the ancient paths,

ask where the good way is, and walk in it,

and you will find rest for your souls.

But you said, ‘We will not walk in it.’

The return to classical education is rightly compared to a return to the ancient paths. We want to walk the road that Basil walked, that Boethius walked, that Benedict walked–in fact any great Christian educator whose name begins with a B. Let’s add the venerable Bede. Of course that’s foolish–we should at least add those whose name begins with A: Ambrose, Augustine, Alcuin, Anselm, and Aquinas. For C, there is Clement of Alexandria, Cyprian, Cassiodorus, and Chrysostom. But enough this alphabetical aside….we have many models, however we wish to classify them.

We want to walk the same path all of these walked, following their footsteps. And of course, we follow carrying the cross Christ prescribes, which means we deny ourselves–and lay down our lives for our brothers and sisters. We might call that peak of hospitality.

We should not be surprised that the Lord indicts those in Judah for not showing hospitality. In fact, Jeremiah holds out some sliver of hope to the Judeans, if they would turn back to the Lord and repent in these ways:

If you really change your ways and your actions and deal with each other justly, if you do not oppress the foreigner (or stranger), the fatherless or the widow and do not shed innocent blood in this place, and if you do not follow other gods to your own harm, then I will let you live in this place, in the land I gave your ancestors for ever and ever. But look, you are trusting in deceptive words that are worthless. (Jeremiah 7:6-8)

They did not treat the outsiders well–the “foreigner.” That word in Hebrew could be rendered, the transient, or alien, or stranger or sojourner. In other words, what we ourselves were and remain. We remain strangers in a strange land, and we know our ultimate citizenship is in heaven

Jeremiah takes Judah to task, for tolerating foreign gods. And don’t we do the same? Don’t we tolerate the god Tik and the god Tok? Aren’t they rather foreign gods? And why might I ask, does it take a Jewish atheist (Jonathan Haidt) to convince us that our schools should be phone free and that 12 year-olds should not have a smartphone? You might want to read The Anxious Generation.

Note the irony: the Judeans mistreat the foreigner but welcome their gods. Aren’t we doing the same thing?

Jeremiah says all this before the Babylonians were to come down from the north and destroy Jerusalem (in 586 BC) and exile the Jewish population to Babylon. The state of things was not good, and Jeremiah makes it crystal clear what is going to happen unless there is clear, clean, pervasive… repentance.

Later, in chapter 8, Jeremiah (or the Lord) asks:

Is there no balm in Gilead?

Is there no physician there?

Why then is there no healing

for the wound of my people?

We cannot know what will happen in our nation in the coming years–we don’t have an inspired prophet like Jeremiah to tell us in precise terms what will happen to the United States–but we can learn generally from Jeremiah that pride comes before a fall and that nations rise and nations fall and that everything has a lifespan. History also instructs that people will in the future behave as they have in the past. We are a flower that fades, the Lord endures forever, and his purposes for an eternity.

Augustine

Augustine, the Bishop of Hippo, witnessed and lived through something that shocked the world at his time, not unlike Nebuchadnezzar coming to conquer Judah in 586 BC. Augustine witnessed the sack of Rome–the eternal city–by Vandals who descended upon Rome from the north and sacked it in 410 AD. The remaining pagans in the Roman empire blamed this on the Christians, saying that the Roman gods were judging them since they were abandoned for the Christian faith. Augustine writes a long response in his City of God in which he says that Rome fell as a result of its own internal moral rot and decay. In The City of God, he traces the history of Rome and shines the light on its dark underbelly; he points out that contrary to the criticisms of the pagans, that it was pagan immorality, infighting, and bloodthirst, that resulted again and again on judgment upon Rome. In a bit of irony, he notes that there was only one place where, during the sack of Rome by the Vandals, that the pagans found safety–in the churches.

Augustine spends over a 1000 pages noting the shortcomings and unfilled yearning of the pagan and the fulfillment of that yearning in the City of God that is established among men by the coming of Jesus Christ and his gospel. You have heard people say, “I will go down fighting.” Augustine went down writing.

In those pages Augustine crafts the church’s historical position on culture, re-articulating in this long work of history the parable of tares: the wheat and tares grow up together–Those in and outside of the church are intermingled, sharing a common earth, commerce, and concerns. The church, while distinctly Christian, refuses to compromise its gospel of love and holiness of life; and at times is prophetic and will not hesitate to speak truth to power; but it also serves faithfully in all facets of a shared society–in government, military service, and commerce, always praying and working for the peace of the city. And the church as the City of God always extends an open invitation for all to come in.

Augustine completed his last revisions of The City of God in 423 AD. Just seven years later in 430 AD the Vandals are back–and this time even surrounding and burning his own city of Hippo in North Africa. He dies of a fever while praying as the Vandals continued their pillaging. What did he think, laying there on his bed of affliction, with young men surrounding him, joining him in prayer? Were his 1000 pages written in vain? Just over a hundred years after Christianity was protected by Constantine, was now everything undone, everything lost?

“Christendom has had a series of revolutions and in each one of them Christianity has died. Christianity has died many times and risen again; for it had a God who knew the way out of the grave.”But the first extraordinary fact which marks this history is this: that Europe has been turned upside down over and over again; and that at the end of each of these revolutions the same religion has again been found on top. The Faith is always converting the age, not as an old religion but as a new religion.

The Church had any number of opportunities of dying and even of being respectfully interred. But the younger generation always began once again to knock at the door; and never louder than when it was knocking at the lid of the coffin in which it had been prematurely buried.

There with Augustine as he lay dying were several of the younger generation, including Heraclius a young priest, who would become bishop of Hippo after Augustine. So was Possidius, who would later become a bishop in nearby Calama. Whatever Augustine thought, all was not lost, nor is it now, nor is it ever, even when judgment looms.

Augustine in The City of God (Against the Pagans) avoids both the wringing of hands (even after the sack of Rome) and a presumptuous proclamation of a universal triumph of the church. Instead he says that the City of Man and the City of God must coexist intermingled. Augustine believed the church would triumph but not universally until Christ returned at which time it would be revealed not only as universal but eternal. Until Christ returns, the wheat and the tares will grow up together; other parables teach us that church will be like leaven working through a loaf of bread, and like a mustard seed that grows into a large tree that welcomes the birds into its branches. Beware the pessimistic confidence that all will get worse (which is despair). Beware the cocky triumphalism that insists all will get better (which is presumption). Augustine holds forth against both these extremes eschatological hope.

Augustine had witnessed the growth of the church in his own life and the century before his birth. The church, heavily persecuted for 300 years, only grew like that mustard tree, as the blood of the martyrs was seed for the church to grow in a thousand places. Rome eventually was exhausted persecuting Christians; they kept multiplying even as Rome tried to suppress the faith. Augustine was born in 354 AD. Christianity was only tolerated and eventually privileged 40 years prior to his birth by Constantine the Great in 313 BC (the Edict of Milan).

What happened during those first 300 years? Persecuted Christians were spread far and wide like seeds on the wind (we call this a diaspora–for spora means seed). Wherever they fled (because of the regular persecution), they loved Christ and neighbor, such that even early on in the book of Acts we read of how the watching unbelievers marveled at them, saying “How they love one another!”

This is the great central story of the Christian church, despite all her imperfections: Christians love one another, and like the mustard tree that begins as a small seed, they grow as a collective tree, and they welcome others to come and nest in her branches–just as even the enemies of the church were welcomed into the churches for safety when the Vandals stormed through Rome in Augustine's day in 410.

The Christians in those churches in Rome in 410 AD, huddling there for safety, made room for the unbelievers. There they were, believer and unbeliever, in the sanctuary of the Church, leaning on its everlasting arms (and I bet in those moments many of the pagans prayed to the Lord Jesus Christ).

The parable of the mustard tree is a parable of hospitality. We offer those outside the church to come live with us–in our branches, in our churches, in our homes, in our schools. For better or worse, regardless of the coming trouble, we invite all to come, even as we were invited to come. We invite people in when it is sunny, but certainly during the storms. Even if we must say “Come and die with us” we invite people in because the secret is that we don’t really believe death exists.

In fact, even when they declare that they hate us, we invite them in because after all we have been praying for them regularly, and love them. Yes, we love our enemies.

Basil and Boethius

It was this strange love that compelled Basil the Great of Cappadocia to start the first orphanages and hospitals in 370 AD, spending his own inherited wealth, the wealth of donors, and the wealth of the church–caring for and offering healing to all–Christians or not–and infuriating the emperor Julian the Apostate (during his brief reign)--Julian who witnessing the charity displayed by Christian realized that such sacrificial love and hospitality was drawing many from paganism to the Christian faith.

It was the strange love of Christ that compelled Boethius in 524 AD to quietly write The Consolation of Philosophy in a prison cell after his world was turned upside down and he was displaced as the second most powerful man in the world (as consul to the emperor) and thrown in a prison where he then was executed after writing the Consolation.

Benedict

It was the same alien, strange love that compelled Benedict in 500 AD to flee his university studies from a corrupt Rome and go to nearby Subiaco to pray in a cave for three years until he started the first Benedictine monastery that preserved learning in the context of community and regular prayer, worship, and labor.

As the barbarians swept through Italy, Benedict set out to Subiaco simply to save his soul. Did he know he would save Europe? I have seen the cave where he dwelled, in a cliff side, praying for those years. What did he hope for? What did he think he could do about the rampant corruption of Rome or the swarming barbarian hordes wreaking havoc with the former stability of Roman rule?

Benedict died in 547 AD. having started 12 monasteries, each beginning with 12 monks, and each containing its own monastic school. He died in Monte Cassino where he is now buried. As Europe entered into a barbarian age, these monasteries spread, monastery by monastery. Those who wanted their sons to get an education often brought their sons to the monasteries as they became virtually the only places where learning was preserved and nurtured. 700 years later, Thomas Aquinas himself was placed in the school and monastery at Monte Cassino, dropped off by his parents at age 5 (a Kindergartner) and leaving at age 14.

Benedictine monasteries offered hospitality, stability, community, education, worship, and served the surrounding areas. They became hubs, centers of learning, life, agriculture, arts, science, and even commerce. Yes, they sometimes brewed beer.

How many Benedictine monasteries (most with schools of some kind) do you think there were by about 1300? The estimates range from 20,000 to 37,000, most of them of moderate size. How did they spread so quickly? Each monastery was designed to plant another monastery. Once 12 monks could be sent forth, they were. They kept giving themselves away. The application: Your school should be a school-planting school no matter your present size and no matter when it will happen. Your school should have an answer to this question: Under what conditions will we help start another school?

Yes, the monasteries at times were in need of reform and there were times of decline and some notable corruption (usually on account of too much growth and success) and then times of internal reform and revitalization. Yes, by the time of the Reformation, there were too many examples of decline and corruption. But for about 1000 years monasteries provided the Christian education of Christendom. Name a great Christian thinker from between 400 and 1300 AD and 9 times out of 10 they were educated in a monastery: Benedict, Augustine and Basil all started monasteries; Cassiodorus, Venerable Bede, Alcuin of York, Anselm of Canterbury, Peter Abelard, Thomas Aquinas, Hugh of St. Victor, even Erasmus–all were educated in monasteries.

If you have read The Rule of St. Benedict, you know that Benedict commanded hospitality in chapter 53. He has a theological justification for this:

All guests to the monastery should be welcomed as Christ, because He will say “I was a stranger and you took me in (Mt.25:25). Show them every courtesy…The greeting and farewell should be offered with great humility for with bowed head and prostate body all shall honor in the guests the person of Christ. For it is Christ who is really being received.

The education of Europe for 1000 years was based on Matthew 25 – on this kind of Christian hospitality. Christ has shown hospitality to us, he has come to us, he has become one of us, he even bothered, we might say, to learn our language. And then he invites us to a table. He then tells us to show hospitality to him by inviting the stranger in, by clothing him, by feeding him. Can we not also say by educating him? That is what the Benedictines did. They were there at the beginning of the University at Oxford, along with monks who were Dominicans and Franciscans. The beautiful green quads we see at Oxford and so many beautiful colleges? They were first monastic cloisters. These monastic schools, by the way, reveal the best way to construct a school: around a garden.

Conclusion

What balm do we have to offer as classical educators in the body of Christ? Do we have a Benedict option? In the most important Benedictine sense, no, because hospitality is not an option, as Benedict imposed it as a rule. We welcome everyone as Christ, and for this we will be judged–for Matthew 25 is about the last judgment, when all the nations will be gathered. And we know ahead of time what is on the test, we know precisely what questions will be asked.

When I was a stranger did you invite me in?

No, but we needed $8500 per child to fund our school, and your parents did not have that money. No, but you had a learning disability and we did not have the resources to educate you along with your siblings. No, but we needed to ensure that students who come our way are academically ready–and you were not. No, but a student must have a credible Christian testimony and yours was weak. No, but one parent must be a church member in good standing, and your mom was a single parent, and had switched churches a good bit…

But how can we do this? Well–wisely, prudently. Benedict would invite anyone into the monastery, but the monastery did have a rule. If you wanted to come in, you had to commit to this rule, and you would be let go if you did not keep it.

We also prepare a table according to our ability–to whom much is given much is required. Are you a teacher? Prepare the table of your classroom. Are you a head of school? How can you be generous? Are you gifted with much wealth? How could you fund the start of a school or a network of schools?

You likely have many good questions about how to show hospitality to the least of these–which should be carefully considered. But the critical question has already been asked by Christ: When I was a stranger did you invite me in? When I was sick, did you care for me? Will you have an answer to that question or an excuse?

"For the Lord your God is God of gods, and Lord of lords, a great God, a mighty, and a terrible, which regardeth not persons, nor taketh reward:

He doth execute the judgement of the fatherless and widow, and loveth the stranger, in giving him food and raiment.

Love ye therefore the stranger: for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt." Deuteronomy 10:17-19

This was my Bible reading this morning. I am currently reading "Mere Christianity" for my book club and I highlighted that very excerpt about course correction. Love it. What an excellent essay and intro into the history of the Church, thank you! This is something I very much want to dive into. I became a Christian at the age of 22 and had no religious upbringing, thus I was and remain ignorant of much. I have 5 children (ages 8 and under) whom I homeschool, and I am wanting to delve deeper into the roots of my faith so I can cultivate this generational walk down the path of life. Do you have any book recommendations? I am not intimidated by a thick and difficult level of reading. I'm ready to stretch my thinking.

Surely our gospel rescue missions (Christian homeless shelters) must morph into this hospitable, working, praying, educating, healing, monastic rhythm.

-Doug Bodde (City Union Mission Kansas City, MO - Adult Education Leader)