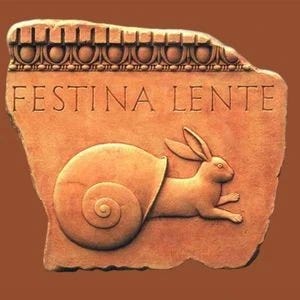

Festina lente in Latin means Make Haste Slowly. It is a principle that Erasmus thought should be carved in every column, so important was it to contemplate and apply.

Festina lente is paradoxical. How can we make haste slowly? How can we go faster by going slower—doing anything? Many of the deep human realities at first do seem counterintuitive and this is one of them. We have all heard that the greatest person will be the servant of all, and that those who humble themselves will be exalted and those who exalt themselves will be humbled, or that pride goes before a fall. We have heard Christ say blessed are those who mourn and the Apostle Paul say when I am weak then I am strong. These are all paradoxes, and paradoxes describe what is actually real, even if surprising and unexpected. Light is comprised of both waves and particles though we are not sure how this can be; we have minds and bodies though it is hard to imagine just how they harmonize.

Festina lente is one of these paradoxes that characterize not just one segment of life, but multiple ones. It was the maxim of generals and emperors. The Roman army, for example, heeded the wisdom of this principle. The Roman army was famous in its time for regular and thorough practice, preparation, and exercise. In fact, the name of the army in Latin was exercitum–that body of men that engaged in perpetual exercise and training for combat. The Latin maxim was carved in stone and even pressed into coins. Note the butterfly (festina) and the crab (lente) on the coin minted in honor of Caesar Augustus.

As a result of regular, “slow,” and ongoing training the Roman army could battle, win, and conquer with lightning speed. How did the Roman army vanquish so many enemies so quickly? By slow, regular training. By heeding the wisdom of festina lente.

By now you can likely tell that the opening illustration features a rabbit as festina and a snail as lente.

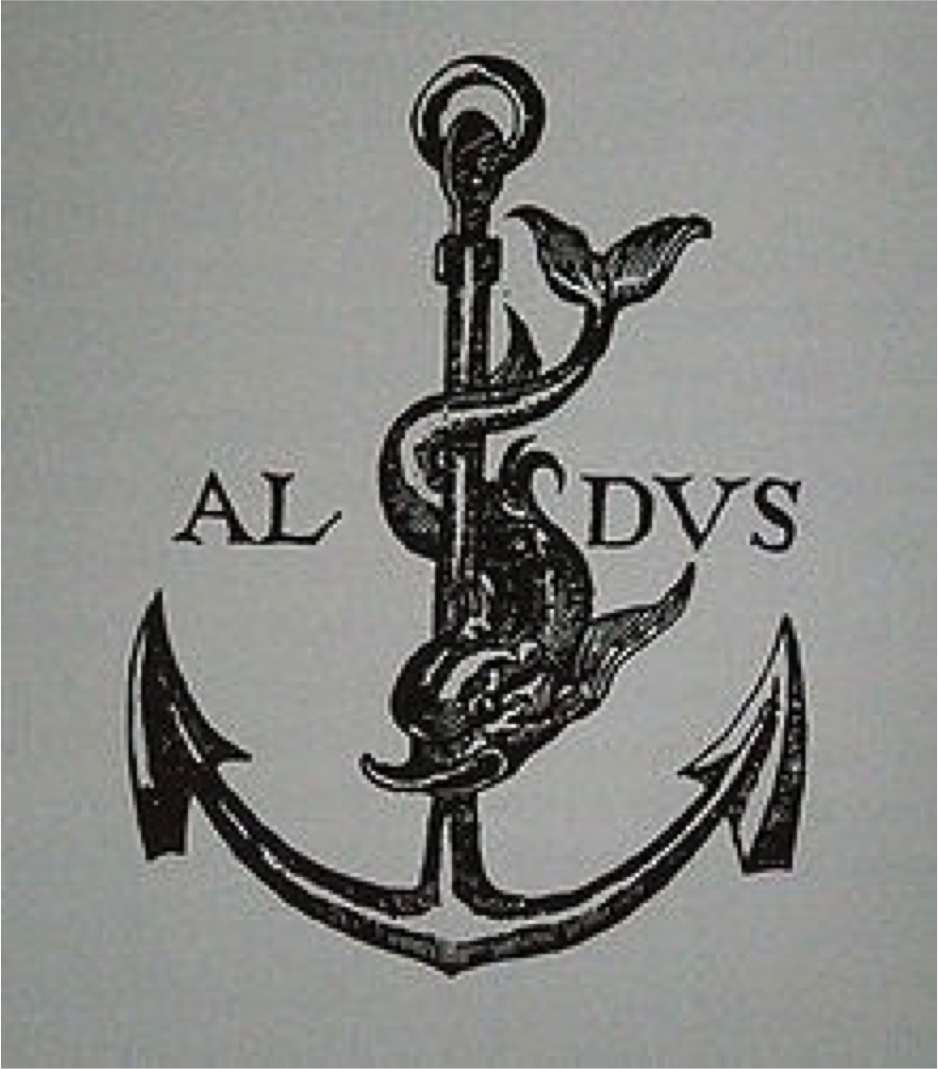

The famous Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius (c.1450-1515) learned that the best way to succeed as a publisher was “to get it right the first time” and take the time to ensure a well-researched, well-corrected, well-edited text, and only then publish it. Aldus became enormously successful but he grew “fast” by proceeding carefully and slowly. He chose the dolphin (festina) and the anchor (lente) for his press logo.

Apparently as his press increased in popularity, Aldus found himself regularly visited and interrupted. Knowing that he needed to focus on his work, he pushed off visitors with a sign: "Whoever you are, Aldus asks you again and again what it is you want from him. State your business briefly and then immediately go away."

We have grown up hearing “haste makes waste” and “measure twice, cut once” and these maxims are corollaries to festina lente. Surely, no army will prepare well by hustling soldiers through cursory training and rushing them to battle. Every carpenter knows the value of careful measuring before cutting. And publishers eventually learn1 to carefully edit a book before going to print.

But festina lente does not merely focus on avoiding waste; it focuses on doing things well from the start, it focuses on mastering what is important in proper sequence. Think of the soldier training in combat, or the carpenter looking over the blueprint, or Aldus carefully comparing Greek manuscripts before printing the first Greek edition of the dialogues of Plato. Each must proceed in prudent sequence echoing another sister maxim: First things first.

Now consider teaching. There is usually a discernible, fitting order to teaching a skill. Just as a carpenter doesn’t start building with the roof, the literature teacher doesn’t start with Shakespeare nor the math teacher with algebra. In every art and discipline, there is a sequence of skills and concepts that should be learned, and it is important to master each skill in order.

In pedagogy, therefore, we discern an important implication of festina lente: master each step or teach to mastery. Violating this principle discourages students and does them unnecessary harm.

Consider math and Latin again. Can students move on to multiplication who have not mastered addition? Can students master addition without mastering math facts? Can students master division without having mastered addition and subtraction? In Latin (or any language) can grammar be taught well without a basic, mastered vocabulary?

Sadly, educators and schools often violate festina lente, to the great harm to students: If students don’t learn to be proficient readers by the end of fourth grade, what can we predict? Dropping out of school before graduation and likely being incarcerated before the age of 30. It is a sobering truth that 70% of inmates in American prisons cannot read beyond the fourth grade level. Why is this the case? Because a student must learn to read in order that he then can read to learn. Students who cannot read in 4th or 5th grade usually become frustrated and stymied, unable to learn well in subsequent grades, increasing in despair until they decide they are not cut out for school and learning. The directive from festina lente would correct this–no student should be promoted to fourth grade—or any grade— until he was proficient in reading. To “go forward” (i.e. social promotion) without mastering the skill of reading is to go backward and do great harm.

As students learn the liberal arts of grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, and music they will find that all of the skills embedded in these arts (or the skills that these arts are) serve one another or that they all dance together. For example, to learn grammar is to learn how words work together to form meaning, and meaningful words are featured (and need to be rightly interpreted) in logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, and music. Rhetoric is the study of persuasive, instructive, and beautiful speech; good geometric proofs are not only logical–they are also persuasive and beautiful to the human mind. This means that mastering any liberal art consists of preliminary study in the other arts. To study logic, is not only to study logic, it is preliminary study in geometry; to study ratios in math is to do preliminary study in music and harmonics.

To slowly master these arts will make a human being quick-witted, able and prepared for all kinds of good works and vocations. This is because the study of each liberal art leads to facility learning the next and because the study of all of these arts makes learning anything subject come much more quickly. This is why Neils Bohr could say “Give me a student that has learned his Latin. I shall be responsible for his chemistry.” By this he understood that previous study in classical language was a superb and preliminary study in… science.

In summary, within each art there is a sequence of skills, ideas, or facts that should be mastered before proceeding forward to ongoing learning. A good teacher will ensure mastery of each step before moving on to the next. She should not waste time in meaningless activity but nor should she push or rush forward simply to move through a text that contains more content than a student can rightfully master in a given span of time. A student who takes time to master each step in academic study will save exponentially more time in the future and far surpass those students who bound forward like the hare while bypassing deep and permanent learning. Let him who has ears to hear, hear, and make haste slowly.

If you enjoyed this article, you can also view a lecture on the subject available on ClassicalU.com, here. It is part of a course on classical pedagogy on that platform. I am also glad to report that I am collaborating with Carrie Eben on a forthcoming book on the pedagogy. As we are working on the book together, I plan to release more articles here on Substack on the classical pedagogies.

I say this as a publisher who learned this the hard way. In the early years of Classical Academic Press, we thought we could edit books sufficiently by passing books back and forth between co-authors. Our readers quickly schooled us and we slowed down (and hired a first rate, full-time editor).

Many students at Magdalen College struggled with math and science.

In math I found it very helpful to teach Book I Proposition 2 to mastery by ensuring that every student could direct the proposition blindfolded. This built up their imagination and also taught them how abstract thinking is not "picture thinking."

In science, George Stanciu focused on Newton's three laws of motion to mastery. Most physics texts in high school and college briefly state the three laws and then go on to numerous other topics. Most physics students misunderstand the laws, especially the third law that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. By the common misunderstanding of the third law of motion, nothing would ever move. After a year teaching physics in Brazil, Richard Feynman proclaimed at a large gathering that "No physics is being taught in Brazil." He demonstrated that the most favored physics text book had fake experiments and everywhere in the book there was word games and not real science. In one example of rolling a ball down an inclined plane, an incomplete formula was used that ignored rotational inertia making the calculated velocity of the ball 33% faster than the velocity of a real ball rolled down the inclined plane. During his speech he randomly put his finger in the book and showed how the book talked about triboluminescence but gave the reader no understanding nor example of it.

“I have discovered something else,” I continued. “By flipping the pages at random, and putting my finger in and reading the sentences on that page, I can show you what’s the matter – how it’s not science, but memorizing, in every circumstance. Therefore I am brave enough to flip through the pages now, in front of this audience, to put my finger in, to read, and to show you.

So I did it. Brrrrrrrup – I stuck my finger in, and I started to read. Triboluminescence. Triboluminescence is the light emitted when crystals are crushed…

I said, “And there, have you got science? No – you have only told what a word means in terms of other words. You haven’t told anything about nature – which crystals produce light when you crush them, why they produce light. Did you see any student go home and try it? He can’t.”

“But if, instead, you were to write, ‘When you take a lump of sugar and crush it with a pair of pliers in the dark, you can see a bluish flash. Some other crystals do that, too. Nobody knows why. The phenomenon is called ‘triboluminescence.’ Then someone will go home and try it; then there’s an experience of nature.” I used that example to show them, but it didn’t make any difference where I would have put my finger in the book – it was like that everywhere.

(Richard P. Feynman and Ralph Leighton, Classic Feynman : all the adventures of a curious character, 1st ed. (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006). pp. 223-224. (emphasis added))

Also applies to physical training -I would rather my clients do one slow controlled proper form of an exercise than rush through 10x sloppy versions.