What Is Wisdom?

It Sounds Nice but Who Knows?

Every man has forgotten who he is... All that we call common sense and rationality and practicality and positivism only means that for certain dead levels of our life we forget that we have forgotten. All that we call spirit and art and ecstacy only means that for one awful instant we remember that we forgot.

—G. K. Chesterton

This article is adapted and expanded from a section on wisdom from my new book The Scholé Way: Bringing Restful Teaching and Learning Back to School and Homeschool.

Many have noted that our age is an age of historical amnesia. In many ways, we have forgotten from where we have come. Most recently this was noted by the French writer Eric Zemmour in his article “Saving Christian Europe” in the June/July print edition of First Things. As we have forgotten our past, it follows that we have forgotten the meaning of words that the past has passed on. One such word is “religion.” We now think of “religion” in comparative terms, as worldviews that we can line up side-by-side for a disinterested analysis. Religion is also regarded as a private matter, generally to be tolerated as long as one’s religion does not lead you to address the public square.

But the word “religion” used to have other important connotations. It used to be that one’s religion not only informed how you addressed the public square (as well as your neighbor)—it was also regarded to be that which holds a civilization together. This is Zemmour’s point in his First Things article. Europe became Europe by being Christian. A Europe without Christianity will cease to be Europe.

Even the etymology of the word “religion” suggests this cohesive role. “Religion” comes from the Latin religio, which is likely related to the verb religare, “to bind again,” “to bind fast.” Think of our word “ligament” as a binding tendon within our own bodies. Religion is at root what holds a society together. What has happened to those societies that have sought to jettison all religion?

We would be wise to read our history, and certainly we would be wise to recover some lost words. I have argued this is necessary to recover a true and robust education and written about this here and here as well as in this podcast.

Another word we would be wise to recover is “wisdom.” It is another one these words like “liberal” and “art” and “liberal arts” that we use without a deep sense of their meaning. What are the liberal arts? Can you name them? Why are they called “liberal”? Why are the called “arts”? Why not “sciences”? What is the difference between and art and science? Most of us don’t know.

Try now to imagine yourself in front of a class in which a student asks, “What is wisdom really?” How would you respond?

In the classical tradition, “wisdom and virtue” are often cited as the chief ends of an education. If you are a classical educator, surely then you should know what wisdom is if it is the chief thing we are seeking to cultivate in our students.

Our word “wisdom” comes from the old English wisdom and is related to the Old Norse (visdomur) and German (Weistum). Our word “wisdom” has taken on a wide range of meanings, so we should take some time to specify what we mean when say that we are seeking to impart it to our students. As is often the case, it is helpful to go the Greek and Latin where we find four words (two in each language) that were used to describe “wisdom.”

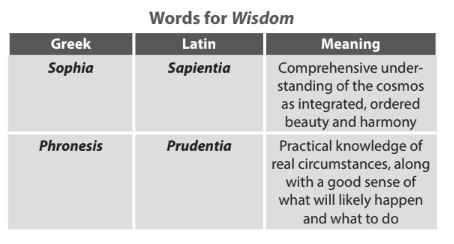

There are two Greek words for wisdom–one is general and comprehensive, and one is more restricted and practical. We might call the first “cosmic wisdom” and the second “practical wisdom.”

Sophia (Cosmic Wisdom): The comprehensive, integrated way that all the parts of the cosmos fit and work together as an ordered, beautiful harmony. From sophia and the adjective sophos (wise) we get English words like “sophisticated,” “philosophy” (the love of sophia), and “sophomore” (a wise fool).

Phronesis (Practical Wisdom): The practical knowledge of what is actually the real state of affairs in any given circumstance along with a sense of what is best, therefore, to do. We get the rather rare academic word “phronetic” from phronesis.

As well, each of these Greek words has a corresponding Latin translation:

Sapientia (for sophia): When used as a translation for sophia, it means wisdom in very much the same way sophia is defined above. We get our word “sapience” from sapientia.

Prudentia (for phronesis): As a contraction of providentia, it can mean “a foreseeing” and also “practical judgment,” “good sense,” and “discretion.” Quite obviously, we get our word “prudence” from prudentia.

We can summarize these meanings in a table:

We can note that phronesis/prudence is also considered one of the cardinal virtues. It can be considered chief among the cardinal virtues since as the virtue that understands what is real, it informs the way the other cardinal virtues will be exercised–only after discerning what is actually real can we act effectively in the world.

This introduces some ambiguity to the phrase “wisdom and virtue.” Isn’t wisdom (if we mean prudence) already a virtue? Why not simply say that “virtue” is the end of education, and then explain (at some point) that “virtue” includes wisdom? But then which “wisdom” do we mean–sophia or phronesis?

In fact, both phronesis and sophia can be regarded as virtues because to have them is to become an excellent human being. Certainly there is nothing intrinsically wrong with saying that the chief end of education is virtue and then explaining that wisdom (both versions) is the highest virtue. Nor is there anything intrinsically wrong with using the phrase “wisdom and virtue” and then explaining that we include wisdom in the phrase because it is the chief or pinnacle of all the virtues.

Certainly to attain the wisdom that is sophia is a life-long endeavor that one never masters. A man may be relatively wiser than others but no man is supremely or completely wise. This is taught to us by Socrates and Solomon, and the Christian must confess that Christ alone is the power and wisdom of God.

Before the Christian era, Aristotle noted that wisdom is the possession of the gods, that men can only relatively acquire. To be wise (sophia), therefore, was to more closely approximate the status of the gods. He also taught that to acquire prudential wisdom (phronesis) takes a great deal of time and experience, learning to “see” reality and discern circumstances in order to know how to behave virtuously (excellently) in those circumstances. Children and youth, because they lack the experience that give us the eyes to see, cannot be virtuous or wise–both come with time.

After the incarnation of Christ, wisdom takes on new dimensions, because of the revelation and teachings of Christ. Christ shows us prudential wisdom in his words and actions–he always knows what to say and do in every circumstance. To grow prudentially wise, then, a Christian must seek to follow Christ, to study Christ, to be like Christ, to be his disciple.

When Paul calls Christ “the power of God and the wisdom God” he does not use phronesis but sophia. Note the passage below (1 Cor. 1:18-25, NKJV) with the Greek words added in parentheses.

For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. For it is written:

“I will destroy the wisdom (sophia) of the wise,

And bring to nothing the understanding of the prudent (sunesis).”1Where is the wise (sophos)? Where is the scribe? Where is the disputer of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of this world? For since, in the wisdom (sophia) of God, the world through wisdom did not know God, it pleased God through the foolishness of the message preached to save those who believe. For Jews request a sign, and Greeks seek after wisdom (sophia); but we preach Christ crucified, to the Jews a stumbling block and to the Greeks foolishness, but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom (sophia) of God. Because the foolishness of God is wiser (sophos) than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men.

In this passage Paul is thinking of Greeks like Aristotle who seek after wisdom (sophia); Paul is very much aware of this Greek philosophic tradition. Paul does not criticize the search for wisdom–he simply asserts that the search culminates in the death and resurrection of Christ. Christ becomes the Ideal Man that the Greeks sought to become; the Christian gospel claims that rather than man ascending to the Ideal, the Ideal has come down to man.

This adds a new and radical dimension to the educational philosophy of the Christian. Christians must study in light of the resurrection of Christ who is the power and wisdom of God; Christians must regard Christ as always the true teacher in their midst that makes all study a prayer to the truth and to the one who is Truth.

Thus the move from the Greek tradition of education to the Christian one is not usually one of clash and collision but one of supersession and fulfillment.2 The Christian student can subsume or take in much of Plato and Aristotle–like the search of wisdom–but both his means and ends are transformed by Christ who is the wisdom of God and who gives wisdom generously to all who ask (James 1:5).

Sunesis is yet another Greek word for practical wisdom that is very close to phronesis. Sunesis is “the faculty of quick comprehension,” “mother-wit,” and “sagacity.”

There are certainly some places where Greek philosophy and education clash with the Christian faith (like Plato’s doctrine of pre-existent souls, and the eternal existence of matter in which God had to reshape into the cosmos) but in many respects Greek ideals were welcomed into the Christian faith though subject transformation. For an exploration of how Greek (and Roman) thought were subsumed into the Christian view, see Louis Markos, From Achilles to Christ, and Myth Made Fact, as well as Werner Jaeger’s Early Christianity and the Greek Paideia.

Just preordered the new book as it sounds delightful. When is it expected to publish?