The Wise Teacher

Maybe You Are Good But Are You Wise?

I was asked to speak at the Turning Point USA Educator’s Summit this July on what it means to be a wise educator. It was a challenging assignment: It is hard to talk about wisdom when we have forgotten what it is.

Like so many concepts related to education, wisdom remains as a word which we occasionally use but seldom understand. Imagine being called upon to offer pithy definition of what wisdom is, along with the justification for why it should be one of the great aims and fruits of a good education. How would you do? In another post (What Is Wisdom?), I try to define wisdom. In this post, I relate wisdom to contemplation and then contemplation to happiness.

If we don’t know what wisdom is—how can we presume to be cultivating it in our students? As we continue to recover a vital classical education, we continue to recover words and their meaning, for only by doing this do we recover the ideas and practices that comprise such an education. Here is an adapted and expanded version of my presentation at the Educator’s Summit.

The wise educator is the happy educator, and the happy educator is the educator who has learned to see. Learn to see what is true, good, and beautiful—and this will make you happy. Do this repeatedly over time and you will become wise.

Put another way, the wise educator is not merely knowledgeable, but perceptive, contemplative, intuitive. The wise educator knows his times but lives in an important sense outside of time. He’s not time’s fool…he is not merely a man of the age, but a man of the ages.

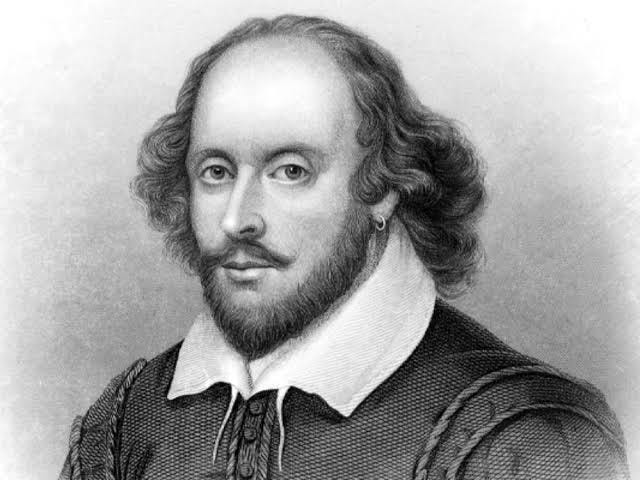

In fact, we can say that the wise teacher is a lover. He is a lover because he is a lover of wisdom, he is a philosopher in the original sense of the word. He is a lover (a philos) of wisdom (sophia). The teacher who longs to be wise will remove anything that blocks his way to the beloved, he will work to remove every hindrance, every impediment. Shakespeare in Sonnet 116 writes about the tenacity of the lover has for his beloved, a tenacity and ardor that will not, as puts it, admit impediments:

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments; love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no, it is an ever-fixèd mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wand'ring bark

Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken.

Love's not time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle's compass come.

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom:[CP1]

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

A teacher who wants to be wise will bear many things during his many hours and weeks, and he will not admit impediments. This is another way of saying that the wise teacher has a measure of fortitude—he is ready to endure storms and other hardships that might push him to the edge. But if he can, and when he can, he will make his pursuit easier by removing barriers and impediments to his quest.

The Roman soldier, too, was familiar with an impediment—for it was the name of the large pack (impedimentum) he carried on his back for mile upon mile. The word literally means that which retrains one’s feet (pedes in Latin) making it hard to walk. Yes, it was hard to keep moving one foot after another with 60 to 100 lbs of equipment on one’s back.

The wisdom-seeking teacher becomes familiar with various impediments. There are many: Wasted time, distraction, frivolous entertainment, unguided reading, dabbling, poor company, poor health. In fact, anything that degrades his mind or body can become a hindrance; the wise teacher soon learns the worth of the ancient and monastic maxim of anima sana in corpore sano (a sound mind in a sound body).

When it comes to teaching, he learns to avoid heavily-scripted curricula that attempt to control how and what and when the teacher will teach; he avoids fast-paced test prep and the “covering” of material that is never mastered, and he rejects shallow books with twisted stories.

Like Shakespeare’s lover, the wise teacher is not time’s fool. He will read the old books (and yes, some new ones), the ones that are ever fresh, ever new, which is why we also call them the great books.

He doesn’t merely read these books, these books read him. And he has read these books patiently: the wise educator has not grown wise in spurts and fits but has grown slowly like a tree—when the fruit is fully ripe it appears quietly and fills the branches without the tree even knowing.

Prudential Wisdom

Teachers mature like fine wine. No teacher becomes wise after two years of teaching, or four years of college, though these can be very good starts, and there are in fact some who are wise beyond their young age. The wise teacher has become so with experience, and therefore time, but also the wise use of time, time spent reading (which is to live other lives before one dies), time spent in conversation with colleagues (which includes students), and time spent star-gazing, meaning not just the stars that burn like flames in the sky (well they are flames in the sky) but any burning wonder that is worthy of attention—Augustine is a star, Aquinas is a star, Shakespeare and Whitman are stars, Dickens is a star, Chesterton is a star, Tolkien and Lewis are twin stars.

The wise teacher is a prudent teacher that has learned how to see what is really real and who helps his students to realize1 what is true, good, beautiful, and holy. The prudent teacher may be busy (maybe too busy) like King David was busy. But King David, busy executive that he was, still found time to be a poet. And in one of his poems, he expresses the persistent longing for an activity far better than exercising his kingly duties. In Psalm 27 he writes that he wants only one thing—one thing he asks of the Lord—that he might dwell in the temple of the Lord all his days and gaze upon the beauty of the Lord all the days of his life. David longed to be in the temple, infusing our word contemplation with sacred meaning (cum + templum). The wise teacher contemplates.

The Latin word for practical wisdom was prudentia (and in Greek phronesis). Prudentia is one of the four cardinal virtues (along with justice, temperance, and fortitude). The wise teacher is prudent without being prude;2 he is providential in the sense that he can see things before they happen, so good is he at reading the circumstances that surround him. Providence (to see before) has collapsed into Prudence—and this ability to see what is really real, to discern, we can also call practical wisdom. If we don’t truly see what is real—how well will we conduct ourselves in the world, how well will we teach? If prudence is the art and virtue of seeing and discerning the real—then who will teach me to see? Who will take me before the true, good, beautiful, and holy and say: “Behold!” Who will instruct me by fixing and holding my gaze, until I become what I behold? Is this not the call of Christ in Luke chapter 6 when he says “When a student has become fully trained he will become like his teacher?” Is this not the embedded truth in the preceding question when he asks, “If a blind man leads a blind man, won’t they both fall into a pit?” A wise teacher is one who has seen something true, good, and beautiful but refuses to simply bring a report to his students. Instead, he takes his students by the hand and says, “Come, let me show you something” --the same impulse of the woman at the well (in John 4) who said to her neighbors “Come see a man who told me everything I ever did.”

Prudence is about sight, and not just physical sight but insight, the perception of what is real. If we become prudent, then we can teach. If we become prudent, we will know what is what, who is who, and what to do. To use Christ’s language again, if we learn to take out the plank from our own eye, we will see clearly to pull the speck from our brother’s eye, from our student’s eye.

Only the prudent teacher can teach justly, giving to each student his or her due. Only after perceiving the reality of the subject he teaches, the class dynamics, the talents, strengths, and weaknesses of each student, the time he has available to teach (and many other factors) can he bring about justice in the classroom—teaching the right art, at the right time, in the right manner, to the right students. Prudence, after seeing the real, will know what to do, when, and how. How do we get prudence?

Aristotle is right when he says that prudential wisdom comes from experience as well as training.3 Children, he says, cannot be prudentially wise, for they have not lived enough to learn and see how the world works. Instruction contributes to the acquisition of prudence but so do the various ways that we are schooled by thousands of observations and experiences.

Acquiring prudence activates and enables other great virtues—like temperance. Knowing the real, the prudent teacher will know how to curb or reign in his own desire to teach far more great content than his students are able to absorb and learn. He will temper his teaching. He will also know how to cultivate temperance in his students—since temperance also doubles as an academic virtue. Some students are intemperate by being lazy and need to be spurred, prompted, and exhorted; some students are intemperate by bounding ahead in their studies before they have truly mastered what is before them—and they need to be pulled back.

The prudent teacher will also know how to cultivate courage—evoking it in himself as well as his students. Students are often tempted by fear, cowering before a new concept, skill, or idea that they think is too hard, or beyond them. Sometimes they fear failure, or looking silly before their peers. The prudent teacher knows when students in fact can rise to meet a challenge, and thus grow their confidence and joy in academic work. He knows how to inspire and gently push, to bend without breaking. He knows how to do this with colleagues who are new teachers, and indeed he knows how to do this even with himself.

Sophic Wisdom

But the wise teacher is not only prudent or practically wise—He is also sophic. We might want to say sophisticated, or even sophistic, despite the bad reputation the ancient Greek sophists have given to this word. But there is a rare word that fits: sophic. The Greek word for prudential wisdom was phronesis, but the Greek word for cosmic wisdom was sophia. Sophia the noun, and sophos the adjective, live (with various meanings) in our words, sophisticated, sophomore (not just a second-year student at college but a sophos-moron or a wise fool), and in our word philosopher (who in the ancient world was a lover of wisdom). It also lives in the name Sophia, the name of my daughter-in-law, whom my son Noah was wise to marry.

To have prudence is to be practically wise, to have Sophia is to understand (as far as a man can) how the world works in every domain and relation. It is the Big Wisdom. It is the ways of God with man. It is at the heart of the questions that God asks Job, when Job finally gets his day in court with God: “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? Have you come upon the fountain of the sea and walked in the tracks of the deep?

How do we obtain even a measure of this grand wisdom of God who knows all things, and in whom all things cohere?

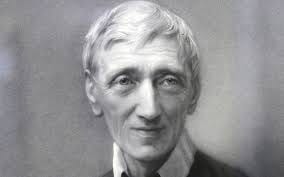

The short answer: A long-lived life during which one has been well-educated. It comes through a life of reading, study, and conversation with mentors, coaches, colleagues and friends. Here is John Henry Newman describing the fruit of a sustained, good education. He calls this “the perfection of the intellect” which does not indicate a flawless or even the best intellect, but one that has fully matured over time.

The Perfection of the Intellect

That perfection of the Intellect which is the result of education, and its beau ideal, to be imparted in their respective measures, is the clear, calm, accurate vision and comprehension of all things, as far as the fine mind can embrace them, each in its place, and with its own characteristics upon it.

It is almost prophetic from its knowledge of history; it is almost heart-searching from its knowledge of human nature; it has almost supernatural charity from its freedom from littleness and prejudice; it has almost the repose of faith, because nothing can startle it; it has almost the beauty and harmony of heavenly contemplation, so intimate is it with the eternal order of things and the music of the spheres.

I have italicized various phrases worthy of our attention. The well-educated mind has a vision of all things–the ways the various elements of the cosmos are harmoniously connected. That vision is characterized by clarity, calmness, and accuracy. The well-educated mind knows the human heart and soul because it has studied history and literature. This makes the mind prophetic (what has happened will likely happen again) and able to discern the heart of any man that appears before him (he has read and become familiar with many hearts in many poems, novels, and stories). The well-educated mind has a proper, broad perspective that can recognize truth from any source without being pigeon-holed by the latest intellectual fad. Such an educated person is at peace, seldom surprised by any opinion or event, trusting in the One who orders and sustains all things eternally and beautifully.

I know of no other short description that illuminates as well what it means to be educated and wise.

Newman, in this passage, is describing not merely prudence or practical wisdom but sophia, the “comprehension of all things.” Sophia, like prudence, is attained slowly and is never finally attained. In fact, the more you see of sophic wisdom the more it seems to recede before you (except to those who observe you). This is because the cosmos is infinite, and God is infinite, and because even your own soul is beyond any final and complete knowledge (much less your spouse—whom you thought you knew when you got married). If you are a mystery even to yourself, how will you finally know even one other person? How will you exhaustively know a nation, or the history of a nation?

Still a wise teacher can become sophic. This is because though we cannot know exhaustively, we can know truly, and we can make progress. And for Christians, we have a special advantage—Christos is the power and wisdom of God (1 Cor. 1:24). The revelation of cosmic wisdom in the person of Jesus Christ who created the world (and all that is in it) and sustains it, can lead us to wisdom in this earthly life that is otherwise not possible.

Jesus is the Logos, the one in whom all things cohere (Colossians 1:17), and who enlightens every man (John 1:9). Everything that is true, good, or beautiful is an Analogos—derived from him and relation to him. Any truth is related to him who is the truth. Anything good is related to him who alone is the source of the good. Anything beautiful is related to him who makes all things beautiful.

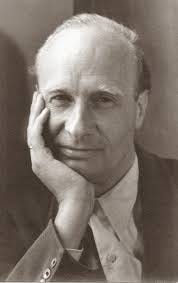

Contemplative and Happy

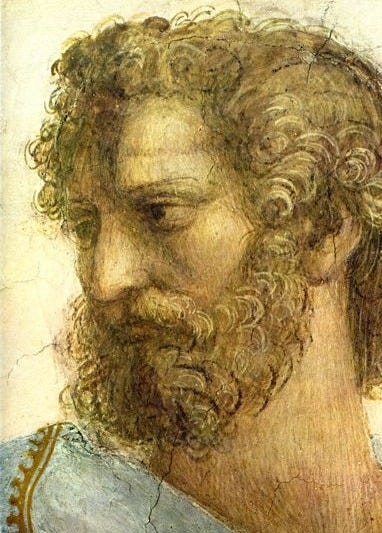

We conclude then that the wise teacher is prudent and sophic—both words worth recovering. Certainly, he continues to seek these virtues. But he cannot become wise in these two ways without that most practical of all human activity: contemplation. Nor can he (or anyone) be truly happy without contemplation. Aristotle notes this in Book X of his Ethics, but I learned this most piquantly from Josef Pieper (pictured above) and especially in his book Happiness and Contemplation.

The wise teacher, therefore, must see the real to be happy and be happy in order to be wise. In this context, seeing reality—or perceiving the true, good, and beautiful—is contemplation.

The word and idea of contemplation is often fuzzy to us because of how little or how poorly we practice it. Perhaps more than ever, we are distracted by distraction to distraction. We likely spend nearly half our waking hours before some glassy, glowing screen or another—those magical devices that bring us inspiration and degradation, blessings and curses, good and evil, but which we are literally unable to turn off (do you even know how?).

But the highest human activity is not entertainment, certainly not amusement. The highest human activity is the unrushed, sustained engagement of our souls with something true, good, beautiful, and holy. It is closely related to wonder—that word we use to describe those times when we are drawn to gaze, consider, ponder, and savor an idea, an object, or an event that evokes astonishment and ignorance at the same time. There is no shortage of such wonders in this cosmos, if only we had eyes to see. We do have such eyes (wonders in themselves!) but they are ever seeing but hardly ever perceiving.

What’s more, our greatest happiness is the result of such wonder-ful seeing, and joy is always the follow-on of happiness. Perhaps this is the most practical truth of humanity and therefore of teaching: Learn to see the wonderful and you will become happy and then experience joy as a by-product.

All of us have experienced the happiness of contemplation even though such experiences are becoming increasingly infrequent. Can you recall a time when you stared in astonishment at some creature, some human face, some plant, some beautiful display in out-of-doors? Can you recall a time when a painting, a poem, a turn of phrase gripped you and compelled ongoing reflection? Can you recall a discovery of an idea or truth that was manifested to you like a secret revelation? Then you have contemplated.

It was Aristotle who first said that it is in contemplation that we are the most like the divine. He said only the gods (who had no need or concern to work for well-being or to satisfy thirst and hunger) could engage freely and regularly in contemplation and thus be blessed. The word Aristotle used for blessed is makarios in Greek.4 The gods were described as the makarioi (blessed ones) and only they could be makarios. But this is the word Jesus uses in the beatitudes in Matthew 5. Blessed (makarioi) are the poor in spirit for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed (makarioi) are the pure in heart for they shall see God.

Even our English translation for makarios suggests something sublime. Our word bless is a dance with our word bliss.5 Are you blessed, then you might be happy, you might even be blissful.

What would happen if our students were regularly taught by such prudent, wise, contemplative, happy, joyful, and blessed teachers? Their very presence would be a more powerful pedagogy than any teaching technique. Such wise teachers would themselves be the most transformative curriculum a school could obtain. One such teacher, as a model, can help to transform a child into a true student, full of zeal, humility, docility, and love for the true, good, and beautiful and the Author of them all.

Perhaps you have had even one such teacher—a teacher who far from being an educational technician, and slave to the script of some published textbook, was a living model of wisdom, someone growing in wisdom, virtue, holiness, and knowledge, someone far beyond the cliché of a “life-long learner” someone more like a muse that radiates love and humility, someone who inspires, kindles, and inflames, someone who takes young minds to gaze on new wonders virtually every week, someone who treats students as fellow sojourners, until they learn to seek and find, even when the teacher is absent.

Would that we all might become that kind of wise teacher—that students might follow us and see what we have seen and then slowly become wise themselves. If this is what their soul and mind long for…let us not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments.

Suggested Reading and Books:

The Idea of A University, John Henry Newman

The Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle

The Intellectual Life, Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods, A. G. Sertillanges

Happiness and Contemplation, Josef Pieper

The Scholé Way, Bringing Restful Teaching and Learning Back to School and Homeschool, Christopher Perrin

The Good Teacher: Ten Key Pedagogical Principles That Will Transform Your Teaching, Christopher Perrin

The Latin words for “thing” (res), “reality” (realitas), and to think (reor) and reason (ratio) are all related. In Latin, one form of thinking is to engage what is real–to “realize.”

Being “prude” until the 17th century was a positive term indicating someone (often a woman) who was wise, discreet, and respectable. Gradually it came to mean someone who was excessively or affectedly modest and proper–similar to what we today call a virtue signaler. Alas, anything good can be corrupted and to be prude now connotes a corruption of prudent.

See Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Book VI, Chapter 8.

See the Nicomachean Ethics, Book X, Chapter 8.

“Bless” is from the Old English blēdsian, blētsian, “to consecrate, make holy, give joy” and “Bliss” is from the related word OE blīths, which means “joy, spiritual happiness, divine joy.”